Scotland’s journey from a highly rural and agricultural nation in the eighteenth century to an urbanised and industrial nation in the nineteenth century is unique in its pace and intensity, a fact commonly reflected in historiography of the period. This short piece will give an overview of this story and introduce some of the themes which I will be focusing on while studying the subject of housing. One example of particular interest to me is the practice of ‘ticketing’ houses which appeared in Victorian Glasgow before spreading to other cities – it is a primary instance of the tension between quantitative and qualitative measures of good living in housing. Additionally, this passage will also give an overview of the ‘fue’ system of land ownership and how this affected the shape and style of working-class dwelling in the nineteenth century. Emphasis should be given to the word overview; this is not a definitive history by any means, rather this is a brief chronology of housing history in Scotland from around 1750 to about 1900 as taken from a few, authoritative sources.

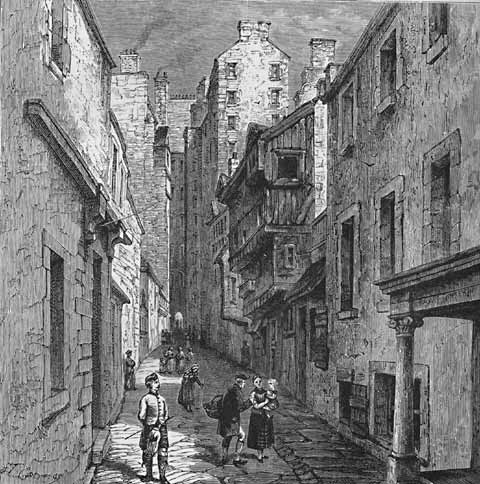

First, it would be helpful to define the term ‘urbanisation’. Urbanisation is a process in which a nation or people begin to live more and more in single settlements, moving themselves from a multitude of small, rural villages (in Scotland’s case, ‘ferm-touns’) into towns and cities. In some places on mainland Europe, this process began in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.[1] Scotland, too, experienced town growth this period as evidenced by maps held in the National Library of Scotland. The comparison between Georg Braun and Franz Hogenburg’s 1583 map Edenburgum, Scotiae Metropolis and James Gordon’s 1647 Edinodunensis Tabulum is stark. Much growth is evident in the density and number of housing units, especially north of Edinburgh’s Lawnmarket where the green spaces of the late sixteenth century had been completely filled over with tightly packed tenements, some six or seven stories off the ground, by the middle of the seventeenth.[2]

Generally, however, the process of mass urbanisation occurred later and much more rapidly in Scotland than elsewhere. The eighteenth century saw the percentage of Scots living in towns of over ten thousand inhabitants more than triple, from 5.3 per cent in 1700 to 17.3 percent in 1800.[3] In 1750 only one in every eighth person in Scotland lived in a town with a population of over 4,000 people.[4] By 1840, the figure had risen to slightly less than one in three living in towns of over 5,000.[5] From 1841 to 1911, Glasgow’s population almost tripled from 275,000 to 784,000; Edinburgh came to host 400,000 residents; and the number of Dundonians grew from 60,000 to 165,000.[6] For the towns and cities in Scotland to have grown so rapidly, however, there must have been some explosive change elsewhere; a great deal of these migrants of the first industrial revolution were those forced off the Lowland farmland to make way for new agricultural practices.[7]

This influx of working people from the neighbouring countryside and, in Glasgow and Edinburgh, from across the North Channel, created high demand for housing. One response to this was the practice of ‘making down’ or subdividing existing buildings to create more housing units.[8] However, if an enterprising housebuilder wished to use this demand to profit, he had to enter into an agreement with the landowner of a type unique to Scotland: the ‘lessor’, the housebuilder, had to provide a down-payment and agree to pay a ‘fue’ to the ‘superior’, the landowner. These fues were life-long: the property would forever remain in the lessors hands so long as he kept up his payments to the superior.[9] This system, in contrast to England where landowners had the possibility of recovering their land and all that had been built on it, meant that Scottish landowners had no vested interest in the quality of housing stock erected on their assets. It also created an incentive for them to ask for the highest amount of down-payment and fue as possible, and, consequently, for the housebuilder to generate returns as quickly as possible. This led to the building of the largest number of units in as quick a time as could be managed. Some housebuilders and landlords also practiced ‘sub-infuedation’, whereby a lessor would charge other housebuilders an even higher duty to build on their land and resultingly spread the practice of cheap, quick and crowded housebuilding. In addition to this, it was common for housebuilders, who were undoubtedly bourgeois but not men with the riches of industrial capital, to finance their projects with bonds made up of multiple different sources of funding and with variable rates of interest, furthering the need for speedy returns on their investment.[10]

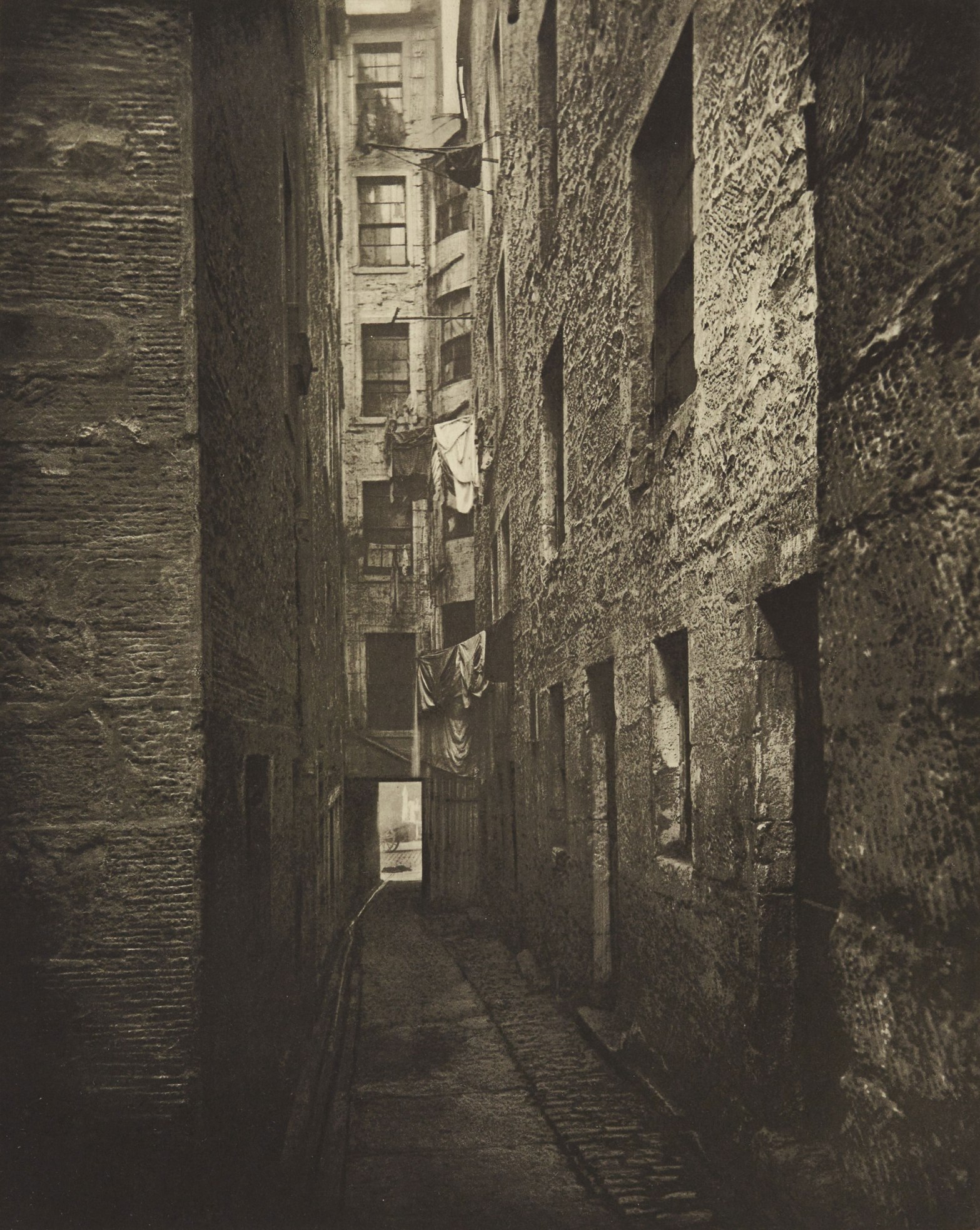

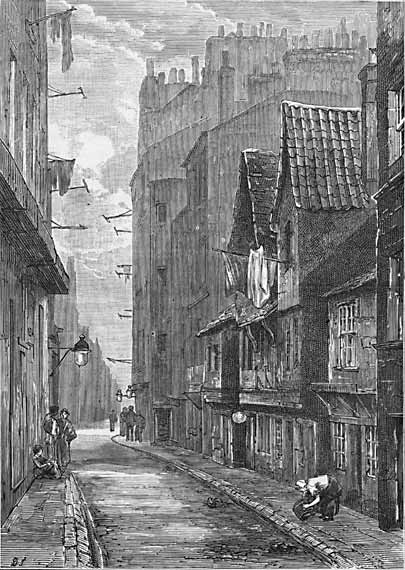

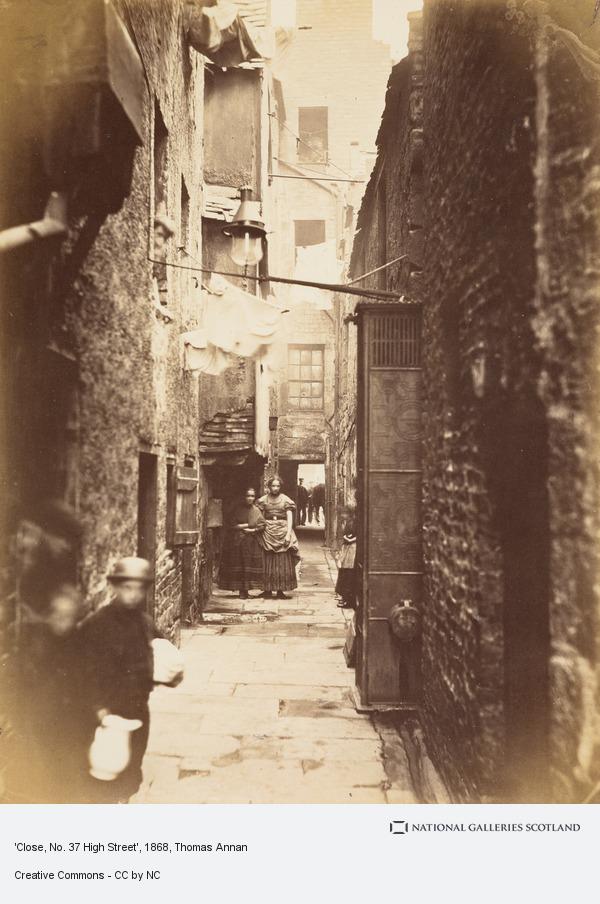

The result was a mass of crowded, dark and insanitary tenement dwellings which circled or invaded the Grecian and Classical architecture erected to showcase the new urban bourgeoisie’s status and wealth. From 1780 to 1850, such striking architectural wonders were erected in the city centres for the headquarters of banks and financial institutions, universities and schools, churches, or as monuments and statues, and adjoining areas became home to the stately residences of middle-class business owners.[11] For the vast majority of people, however, life was lived in a house of one or two rooms in a block of tenement flats; the very worst-off lived in a ‘single-end’ with no windows at all.[12] Neighbourhoods were tightly packed in working-class districts: when the Edinburgh Corporation began to clear some of their worst slums in the late 1860s, it was found that some parts of the city’s Old Town had a population density of up to six hundred people per acre.[13] The health effects of the poor living conditions, sanitation and massive overcrowding in poorer districts had begun to show by the 1840s; repeated epidemics of infectious diseases like cholera and typhoid, encouraged by the rancid water and cramped conditions, brought the national death rate up after years of sustained fall.[14]

Owing in part to these horrifying conditions, coupled with economic downturn, industrial action and the rise of Chartism, a “sense of urban crisis” had spread across Scotland in the 1830s and 1840s. Significant barriers to improvement existed in the structure of local government which from the 1840s to the 1890s had split responsibility for overseeing sanitary and health concerns, making it difficult to co-ordinate efforts to tackle the cities’ problems. Central government was also of little help: laws passed in Westminster to enforce housing standards in 1868, 1879 and 1882 did not make provisions for trying lawbreakers in Scottish courts, mistakes which went unnoticed for years after their ascension to law.[15] Local property capital was also vastly overrepresented in Scottish local government, stymying any efforts for intervention in the market which might have reduced their ability to profit. As late as 1875, of the Edinburgh Corporation’s elected members four-fifths were landlords with a collective number of 1,000 properties between them; in 1905, three-quarters were landlords with 1,300 properties – and this is not even to speak of the membership of the various committees, where landlords could make up to 90% of the membership in the late nineteenth century.[16] Further, the middle classes of Victorian Scotland held several views that prevented effective intervention: firstly, interference with the private free market was held to be at odds with liberal capitalism; secondly, they believed that charitable acts and institutions would be enough to help solve the problems that working-class people faced; and thirdly that the working classes could be divided into ‘respectable’ and ‘unrespectable’ and thus ‘deserving’ and ‘undeserving’ of relief.[17]

As a result, the middle-classes in Scotland used little of their political, economic, social and moral power in society to build or promote the creation of quality working-class housing. Rather, the focus of reform in the Victorian Scottish city often was on sanitation and the provision of services. The Glasgow Water Works Act of 1855 set a milestone for municipal political action. Created to deal with the city’s diseased and polluted water supply, it allowed for the creation of a huge infrastructure project to build a series of pipes which would provide clean water from Loch Katrine. Edinburgh followed with a similar plan the next year and eventually each of Scotland’s principal cities did the same. Edinburgh was also the first city in Scotland to appoint a Medical Officer of Health in 1862 to oversee the enforcement of sanitary standards and inspect the conditions of housing. Glasgow also provided municipally-owned gas lighting from the squares of the city centre to the darkest tenement wynd. In the 1860s and 1870s the city also began to provide municipal washhouses, hospitals and laundromats and, by the end of the century, the addition of Corporation-run tram lines made Glasgow the most extensively municipalised city in the United Kingdom.[18]

The 1860s also saw the appearance of ‘City Improvement Trusts’ in Scotland. These were set up by local Corporations to oversee slum clearance, identifying and destroying the very worst of tenements. For Victorian Scotland, these efforts represented a transgression of private property rights and were not undertaken without controversy. Proposals for slum clearance in Edinburgh sparked debate between moderate and radical Liberals about the policy’s potential breaching of the principal of laissez-faire.[19] In Glasgow, Lord Provost John Blackie lost his seat due to anger over the Improvement Trust’s cost.[20] It should also be noted that these schemes had no provision for rehousing those who lost their homes at the council’s expense. Another popular tactic for ‘dealing’ with the housing problem in the cities was that of ‘ticketing’. Medical Officers or Corporation-employed inspectors would measure the dimensions of each tenement dwelling, calculate the number of occupants allowed per room and visit the dwelling, usually in the hours after midnight, to ensure the limit was being upheld. The name referred to the tin plate which was fixed to the door of the house, bearing the maximum number of inhabitants allowed.[21]

Despite this intractability on the issue of housing, there were some slow but notable improvements by the Edwardian era. After years of building up municipal projects and flexing its muscles in terms of its public spending and regulation, local government had created a somewhat rigorous municipal sector. Local government provision of services had become an accepted and essential part of life in the cities of Scotland, paving the way for later, more extensive council housing schemes. By 1890s, too, the Corporations had consolidated their power structures and gotten rid of the duel parochial-central board system which had hampered progress earlier in the century.[22] Housing stock in the cities had also improved since the mid-century. One-roomed houses, which in 1861 were home to over a third of the Scottish population, were only inhabited by nine per cent of Scots by 1911. However, the proportion of people living in only two rooms had increased from thirty-seven per cent to forty-one per cent; half of all people, then, still lived in two rooms or less. The dire windowless flats, however, had disappeared from the townscapes.[23] Of course, these improvements were nowhere near enough and from the 1890s to the 1920s, rent strikes would break out in multiple Scottish cities over the price and quality of working-class housing.[24]

From this brief passage, we can see how nineteenth century Scottish housing and living conditions were affected significantly by several factors, most prominently: the free-market ideology and liberal values of the urban bourgeoisie; a system of land-ownership, leasing and financing which encouraged the building of tall, dense buildings with small but numerous housing units; and a system of local government which was resistant to change in both political interest and governing structure. I will be exploring this time period in more detail as this project goes on, especially the practice of ticketing houses and its relationship to later uses of quantitative measures of deprivation in Scottish history. I mentioned early on in this post the existence of the tenement form of housing long before the industrial revolution – indeed, this tradition of housebuilding in the nineteenth century seems to be a continuation of practices from as far back as the sixteenth century. These buildings were very tightly packed, at least as dense as those built in the Victorian period. Since these predate the huge expansion of the urbanisation, the emphasis placed on population growth and the subsequent need to house a new, large section of urbanites, though a convincing explanation when applied to the proliferation of tenements in Victorian Scotland, is not sufficient to give reason to the style’s popularity in Scotland, generally. This is an avenue of investigation not covered in my reading and may be an interesting avenue for future researchers.

[1] TM Devine, The Scottish Nation, (2006, Penguin, London) pp.153 – 154

[2] Both maps are available online, here: https://maps.nls.uk/view/00003284; and here: https://maps.nls.uk/view/74475427

[3] Ian Whyte, ‘Urbanisation in Early Modern Scotland: A Preliminary Analysis’, Journal of Scottish Historical Studies Vol 9 Issue 1 (1989) p.22, table 1

[4] TM Devine, The Scottish Nation, (2006, Penguin, London). p.123

[5] TC Smout, A Century of the Scottish People, (1986, Collins, London) p.32

[6] Ibid. p.41

[7] TM Devine, The Scottish Nation, (2006, Penguin, London) p.163

[8] Ibid. p. 341

[9] MJ Daunton, ‘Housing’ in PML Thompson (ed.) Cambridge Social History of Britain Vol II: People and their Environment, (1990, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge) pp.199 – 200

[10] TC Smout, A Century of the Scottish People, (1986, Collins, London) pp.37-38

[11] TM Devine, The Scottish Nation, (2006, Penguin, London). pp. 329 – 331

[12] TC Smout, A Century of the Scottish People, (1986, Collins, London) p.34

[13] PJ Smith, ‘Rehousing/Relocation Issue in an Early Slum Clearance Scheme: Edinburgh 1865 – 1885’, Urban Studies Vol 26 (1989) p.103

[14] TM Devine, The Scottish Nation, (2006, Penguin, London) pp. 166 – 167

[15] TC Smout, A Century of the Scottish People, (1986, Collins, London)p.40 – 43

[16] D. McCrone & B. Elliott, The Decline of Landlordism: Property and Relationships in Edinburgh, in R. Rodger (ed.) Scottish Housing in the Twentieth Century, (1989, Leicester University Press, Leicester) pp.221 – 222

[17] TC Smout, A Century of the Scottish People, (1986, Collins, London) p.51

[18] Ibid. pp.43 – 45

[19] PJ Smith, ‘Rehousing/Relocation Issue in an Early Slum Clearance Scheme: Edinburgh 1865 – 1885’, Urban Studies Vol 26 (1989) pp.103 – 106

[20] TC Smout, A Century of the Scottish People, (1986, Collins, London) p.46

[21] MJ Daunton, ‘Housing’ in PML Thompson (ed.) Cambridge Social History of Britain Vol II: People and their Environment, (1990, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge) p.201

[22] TC Smout, A Century of the Scottish People, (1986, Collins, London) p.42

[23] Ibid. pp. 33 – 34

[24] D. McCrone & B. Elliott, The Decline of Landlordism: Property and Relationships in Edinburgh, in R. Rodger (ed.) Scottish Housing in the Twentieth Century, (1989, Leicester University Press, Leicester) pp.223 – 227