Here I would like to explore the connections between housing and social change in more detail than I did in my previous blog post. The history housing in Scotland cannot be told without an understanding of the social forces and influences at work during their construction, demolition or refurbishment. Housing and status are tightly interlinked in history and through studying the buildings, neighbourhoods and conditions in which people lived, we can also glimpse important information about the development of modern class relations. As we will see, for much of Scottish history, the common house – that available or practicable to working Scots – shared similar structural features: space was undifferentiated and, for most, was divided into only one or two rooms, whether in the rural bothy or salmon lodge of the early modern period or the urban tenement flat of the nineteenth or early twentieth century. Houses, though, are more than the sum of the material and space that make up their physical presence; rural life in pre-industrial times had an entirely different social logic and structure than urban living in the Victorian period, of which house-type and housing tenure were a part. As we will see, social and economic changes significantly impacted the processes of life related to housing, the responsibilities placed upon those looking for housing and the social roles fulfilled by landlord and tenant. Distancing between the middle and working classes is a prominent feature of this period of study and nowhere is this borne out more, outwith the factory walls, than in housing.

Before the agricultural revolution and the subsequent clearances of people from the land in the rural Scottish Lowlands, eighteenth-century rural life was based on a structure of land-ownership in which three main classes predominated. The lairds, who owned the land and rented it out; the ever-decreasing number of renting farmers; and the cottars who were essentially ‘landless’ and who entered into housing agreements with the renting farmers in exchange for their labour. Only the renters paid in money for their access to the land, in addition to providing transport, manpower and tools to their laird when demanded. The renters were also beholden to court-enforceable contracts which made their duties enforceable and enshrined their landed status by law. By contrast, the cottars had only to provide labour during certain peaks in the harvesting season and to assist the renter with their duties to the laird, no cash was exchanged for their keeping of a small plot of land. The nature of these private agreements accorded them no protection through the courts and when the introduction of new agricultural practices extended the amount of time, space and labour needed on the farms, the renters and lairds were able to rid the farmland of these workers with little difficulty. The marketisation of the agricultural economy made the renters more-and-more powerful men, growing to become a strong rural middle class by the turn of the nineteenth century. Now commanding labour by employment, rather than extralegal arrangement, they were made rich through orienting their production toward consumption in the cities and towns. The cottars, once making up between two and three fifths of the rural Lowland population, were ‘annihilated’ as a class, thrown from their cottages to make way for improved agricultural production, becoming new farmland labourers, destitute and homeless in their parishes or migrants to the growing cities.[1]

The quest for countryside ‘improvement’ which brought with it the changes to agricultural practice also brought with it changes to the housing of the rural poor. The cottar’s ‘annihilation’ also saw their small houses subject to demolition and replacement. These old houses were communal and continued a pattern of living which had existed in Scotland for centuries, with life lived in one or two rooms with no fixed use; that is to say that work, relaxation and recreation all happened in the same space. Their replacement, the ‘improved’ houses, were much the same in terms of structure but had more stringent building standards, differed most in the common furniture found therein. With the growth of the money economy in rural areas and the development of industry in the cities, standard furniture and consumer goods began to become more common in rural households. Previously, the most basic furniture was a rarity, but, through the nineteenth century, beds, storage cupboards, catalogue-bought chairs and clocks came to be found in cottages throughout Scotland. By the end of the century, a strange fusion of the traditional and the modern characterised homes of the countryside, whereby the tools of work and the traditional hearth existed in the same spaces as items which extolled status or income.[2]

As noted in my previous blog, Scottish urban development was not entirely concentrated in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries; areas of considerable population density, notably Edinburgh, had developed between 1550 and 1650. However, town and city evolution in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries was relatively uneven. Some larger burghs in the seventeenth century, markedly those close to the ‘big four’ principal cities, experienced significant population decline.[3] Many settlements across the lowlands also failed to achieve a truly urban character – that is, a mature local government administration, thriving industry or a large permanent population – and remained market towns or agricultural settlements in this period.[4] Localities that did grow in this way were able to exert significant control over who was able to practice their crafts within their boundaries and, as was the case with the settlements which had grown around the capital, were engaged in a battle of competition and control with neighbouring settlements over the right to practice crafts or to trade within their bounds.[5]

The quest for ‘improvement’ and the spread of Enlightenment values which had begun reshaping the social landscape of the Scottish countryside were also, at the same time, active forces in the development of Scotland’s urban areas of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. A focus on the reform of manners and on the aesthetics of beauty in architecture saw the burghs of Scotland, from the smallest to largest, lose features considered to be unrefined. This presented itself in the re-fronting of many older buildings in the burghs, especially in removing wooden features and adding stone ornamentation to their facades. Towns across Scotland began to host a wider range of entertainment ventures, such as dance instructors and coffeehouses, and commercial outlets for luxury goods, including silk merchants and silversmiths. Not only is this an indication of a developing interest in the aesthetic and recreational value of the urban environment but is also strong evidence of both the growing disposable incomes of middling sorts and the development of a consumer economy.[6] The rapidity at which the modern market and industrial economy grew in the eighteenth century was hastened by changes in the laws and conventions on trade. Tom Devine points toward the 1672 opening of the right to overseas trade to non-Royal Burghs and to the slackening practices of the trades guilds before 1740 as particularly important factors in the development of the modern money economy. Traditionally, only elite merchants of the Royal Burghs – the Burgesses – were allowed to engage in trade after a long, often seven-year, period of apprenticeship in the guilds followed by the payment of expensive duties. Access to this course of instruction was often difficult for those of middling and lower ranks to access; beyond the expense, the control of admissions was in the hands of established Burgesses who preferred to confer admission to their offspring. This system began to wane by the beginning of the eighteenth century. The opening of trade saw the number of people attempting apprenticeships drop, preferring not to engage in the traditional route to mastery of commerce, instead trading independently. For those who did complete these courses of training, a shorter period of apprenticeship, three to four years was most common, and lower fees for entry were granted to them. These changes represented the coming of a more fluid and competitive market and brought prominence to a number of families from the middle strata of Scottish society, many of whose descendants would become the masters of industry and commerce in the nineteenth century.[7]

Despite the growing interest in the beauty of urban constructions, there were limitations on the reforms to the condition of buildings. Housing in Edinburgh in this period, for example, was built very densely with little space between buildings, owing in part to the limitations imposed upon housebuilding by the walls of the city. Tenement blocks stretched on in rows to the north and south of the Lawnmarket and down toward the Cannongate. The social make-up in these buildings was mixed; aristocracy, merchants, artisans and the very poorest could share the use of a single building, with floor occupancy dependent on the class-character of the tenant: well-to-do families could afford to occupy the sought-after first and second floors; the middling ranks often lived in the highest floors; the very poorest occupied the stories below ground. The furniture found in these homes also indicated class: the middle ranks and above could afford to purchase furniture like beds, chairs and tables and even certain trinkets such as looking-glasses and pottery..[8] If they were lucky enough to have more than one or two rooms, space was still often cramped and rooms continued to have mixed uses, even into the nineteenth century. John Sime, an architecture student, produced a plan of his family’s house in the Lawnmarket area for a project in 1808, showing the layout of the building the furniture in each room. While there is a separate bedroom, granting its occupant a degree of privacy unafforded to the poorer classes, each other room has a bed either folded into a recess or hidden in a cupboard, including the kitchen.[9]

The changes in the social structure of the countryside, the resulting exodus of cottars and other rural poor coupled with the growing industrial economy of the burghs saw that by the year 1800 over one sixth of the Scottish population was living in a settlement of over 10,000 people. This figure would only continue to grow throughout the nineteenth century. The influx of people in need of housing was dealt with by subdividing existing buildings – a practice known as ‘making down’ – or was exploited by housebuilders and landlords, who used these newcomers as a source of capital. The fue system and the system of lending that was common to the housebuilding industry in Scotland encouraged the creation of dense tenement blocks, with ‘houses’ of one or two rooms and only a ‘close’ or alleyway to separate them. The result was that as the population of cities continued to increase, so did the population density: in 1791, Glasgow’s population was 66,000 with an area of 716 hectares, or 92.2 people per hectare; in 1831, the population had risen to 202,462 and despite boundary changes adding an additional 167 hectares of land, the population density rose to 229.2 people per hectare.[10] Between 1831 and 1841, the Blackfriar’s district of Glasgow (today’s Merchant City, University of Strathclyde and Glasgow Cathedral area) saw its population increase by forty percent, but the number of houses in the area remained unchanged.[11] The lack of housing and desperation to find work in the cities coupled with a lack of capital led people to settle for solidly substandard housing arrangements in large numbers; overcrowding in Scottish cities was endemic.

The houses in urban centres which were affordable to working-class Scots were overwhelmingly that of the one-roomed, the ‘single-end’, or two-roomed flat, some of them vacated in this period by the more affluent urban citizens in favour of more spacious housing in the peripheries. Privacy in these quarters was non-existent and the use of space was strictly general. Edwin Chadwick’s 1843 Report on the Sanitary Conditions of the Labouring Population of Great Britain described the practice in Scotland of keeping the body of a deceased loved one in the flat until they were buried, potentially exposing the whole family plus any visitors to infectious diseases.[12] Crowded living conditions are also evident in George Bell’s 1849 tract Days and Nights in the Wynds of Edinburgh. Though concerned mostly with the sanitation, behaviour and morality of the poorer citizenry of the Old Town, and written from a place of self-assured moral superiority over the subjects, descriptions of the living conditions are vivid:

“The chamber which was about twelve feet long, by seven or eight feet broad, was occupied by seven human beings – two men, two women and three children. The men, father-in-law and son-in-law, were seated together at their craft. They were shoemakers. The wife of the old man was seated on the ground, binding a shoe. One small candle gave light to the three. The wife of the young man sat at the fire, suckling an infant; and two children, about two and four years of age respectively, sat on the ground at her feet. We interrogated the men, and found that neither of them were in regular employment; they could not get it, and therefor they worked on their own account, that is, when they could afford to buy leather. The profit upon their labour was so small, that under any circumstances they were obliged to work fifteen hours a day in order to sustain themselves. They seldom or never went out of doors, and their diet was of meagre description.”[13]

These conditions were prevalent in Scottish working-class housing and were unchanged for many throughout the nineteenth century. Despite the slum clearances and various municipal projects aimed at improving the condition of the cities, though notably not at providing municipally-owned housing for workers, squalor was still endemic for many working class families. An 1891 line drawing shows a family of eight living in a single-end with no source of light or fresh air visible. Four of them, two adults and two children, are huddled around the fireplace, three children share a small bed on the right-hand side and an adult male rests on a makeshift bed to the left. The only other piece of furniture visible is a small stool; there are no work tools, decorative features or ornaments. The walls of the house are cracked, and the brick exposed.[14] These terrible, cramped and insanitary conditions represent the living of the very poorest in Scottish cities of the period. More fortunate people, though still living in one or two-roomed houses for the most part, could expect a house with baths, sinks, coal bunkers and worktops built in, but still had to contend with the tight spaces and resulting spread of disease. In these tenement homes, food was cooked over the fire and many houses came with complicated cast-iron hobs and water-heating apparatus, though, for the majority, these contraptions would be scores of years old and seldom brand-new. Some industrial workers could even afford to furnish their homes with whole dining sets and beds, though space dictated that these objects’ size and number had to be limited and often furniture had to be moved around to bathe or unfold bedding. Rarely, either, were beds occupied by just one person, children often shared one and parents the other; in many circumstances whole families occupied a single bed. Alongside the previously mentioned storage of dead bodies, lack of space in tenement houses saw parents engaging in sexual intercourse in the company of their children, children being forced to play in the landings and rooms of the housing block, whole families bathing in the their room on one day per week and the taking of turns to eat dinner at a table with too few chairs to seat every member of the family at once.[15]

Working class people of the nineteenth century also had to contend with moral scrutiny by their social superiors. Landlords, industrialists and merchants were ranked among the elders of the Church of Scotland: evidence from Aberdeen shows that multiple class ‘fractions’ existed within the Kirk, representing different factions of capital, but united in their wholly bourgeois status. For these men, the business and religious world were interlinked. Financial solvency and moral upstanding were one and the same and instances of financial hardship or vice led to investigation and appearance before the Kirk session. For working class people, this meant judgement by a board composed of employers, landlords and shopkeepers, all of whom ranked above them and from whom essential services for living were procured. [16] This moral scrutiny upon the lower classes was also exercised through the system of letting. When one entered into a renting agreement as a tenant, one was not only procuring housing but was also entering into a system of moral, financial and social control with the landlord acting as adjudicator. Landlords often required a character reference from a previous tenant for any new renter. A similar judgement of character was also needed for any ‘tick’, credit from landlords but also from other bourgeois such as shop owners, to be given – and this was often needed, given the seasonal nature and lower wages of certain industries in Scotland. The personal standards examined were diverse. Perhaps understandably, previous rent arrears and indebtedness were taken into account, but a tenant’s punctuality and performance at work, their ability to moderate vices and their temperament were all examined before a rental agreement could be made or ‘tick’ given out. A family’s behaviour and their ability to meet the moral standards of the middle classes were the criteria which allowed them access to the most basic commodity and standards of living.[17]

The landlord’s power, then, was not simply an economic and social power, but a moral and ethical one which was readily exercised to police working-class behaviour. This is not to diminish or minimise the hold that letting agreements gave landlords over their tenant’s material conditions, on the contrary this aspect of the relationship was equally imbalanced. Beyond the ability to raise or lower rents or to charge steep deposits, the landlord also had the ‘right of hypothec’ over their tenant’s property, including everything contained within the home from furniture to work tools. Once entered into an agreement, these possessions were legally the landlord’s and were liable for sequestration if it the landlord felt a tenant might be in financial trouble and about to miss a payment. This differs significantly from other, similar laws in place in England and elsewhere at the time, where possessions could be taken only after debt was accrued. In Scotland, a tenant’s possessions could be taken even before this had happened.[18] Scottish letting was also based on the ‘missive’ – a long term letting agreement which further constrained and controlled the tenant’s actions by confining them to a single property for up to eighteen months, regardless of fluctuations in pay, rates or any misfortune that may befall the family, on threat of legal action.[19]

Life was lived much differently at home for the bourgeois. Their growing capital and social power were being expressed in Scottish architecture as early as the eighteenth century, with the construction of the New Town to house the richer elements of Edinburgh. In each of Scotland’s principal cities, their new-found social status was put on show in the city centres as Grecian and Neoclassical building were constructed to house banking, educational or business centres – foundational institutions which had brought the middle classes such wealth. The spread of shopping ‘warehouses’, analogous to modern supermarkets, also began to appear in the nineteenth century, where wealthy individuals could purchase fine furniture, home decor or clothes among other things which extolled their status.[20] There did exist, for a time, areas where an intermingling of the classes was present, especially in the later eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Aside from the above-mentioned Old Town of Edinburgh, the Laurieston, Gorbals and Hutchesontown areas of Glasgow, fued out for development from the 1790s, were host to a mix of social classes. However, much like the Old Town, social segregation became entrenched: certain streets and sub-areas of these neighbourhoods found themselves occupied more and more by people of the middle-classes and the dual developments of incredibly insanitary conditions and the growth of more spacious and luxurious housing to the West. By the closing decades of the nineteenth century, the Gorbals and its surrounding areas was an exclusively working-class slum.[21]

Glasgow’s West End was built slowly, in pieces from the 1830s onwards to house the cities elite burghers, ranging from lawyers and doctors to industrialists, who sought an exclusivity and fashion in their living arrangements, away from the crowded conditions of the city’s east and centre. A mix of villas, terraced town houses and tenements formed the majority of the stock in this area.[22] Similarly, middle-class tenements and villas were also built in large numbers in Merchiston and Morningside in Edinburgh.[23] These dwellings could be differentiated from working class primarily by their number of rooms, which could number five or more, and by their exteriors which often featured ornate stonework and bay windows.[24] The more generous space offered by these dwellings meant that bourgeois life at home was not constricted by dimensional limitations that plagued the working class. Privacy was available for each member of the family, and areas for work, recreation and rest were clearly delineated. The wealth of the residents and the space afforded to them meant that these middle-class homes featured a great deal of internal furnishings, exotic and curated in the case of the richest. This is evident in photographs from the latter nineteenth century: pictures from the mid-1890s of William Reid’s apartment above his upholstery business in the city’s New Town show a collection of antique furniture, a filled bookcase, walls covered in mirrors and paintings, all set in spacious and light-filled rooms with large windows and decorative ceiling lights.[25] Even more impressive was Arthur Sanderson’s residence in Dean Village, the interior of which was designed by William Scott Morton to reflect a different style of art in every room, with paintings crowding the walls dating from the middle ages onward.[26]

This gulf in material conditions was very much apparent to citizens of Victorian and Edwardian Scotland. By the closing of the nineteenth century Scottish housing had become a site of significant confrontation between landlord and tenant. Frustrations mounted on both sides as a result of the conditions of housebuilding, letting, reform and general living inhibited both the extraction of capital from housing for the landlord and a basic standard of living for the tenant. Landlords had a significant hold on the intuitions of local authority, especially in Edinburgh, but had reluctantly conceded a certain amount of control over the housebuilding industry since the 1860s. They had to contend with building regulations that covered every aspect of the trade, from the rate and quality of bricks laid in a day to the types of tiles used in the roofing, and were prevented from exploiting the areas cleared of slums for the building of new houses. In addition to this, the Scottish building industry was beset by rapid fluctuations in demand which the typically small housebuilding companies found difficult to predict and prepare for, resulting in a great number of bankruptcies, reduced building activity and diminishing capital investment. Landlords and other middle-class city dwellers also shouldered the burden of taxation with rates increasing to pay for a growing number of municipal projects and sanitary measures.[27]

The most significant pressure on landlords’ power and income, however, would come from the tenants. Despite the efforts of the city Corporations to deal with the issue of housing through sanitary reforms and regulation of housebuilding, Scottish housing had hardly improved by the early twentieth century. Slum conditions persisted in the smaller burghs and the enforcement of building codes did not become universal until the 1890s. Landlords and housebuilders often went to great lengths to find ways to bypass them in any case. Overcrowding remained a significant problem: in 1911 over forty-five per cent of the Scottish population lived more than two to a room, with the figure rising to over two-thirds in some of the larger burghs of the central belt. More than half of the housing stock was still composed of only one or two rooms and though the proportion of Scots living in these houses had fallen, the absolute number had risen to over two million.[28] Working class tenants also had to deal with increased scrutiny from their landlord or factor, who, in response to their weakening position, began to intensify use of their ‘right of Hypothec’; in 1909 the amount of rent recovered through the courts was more than triple that of 1899. Further, rates of eviction were high in cities like Glasgow, in which there were 1 warrant of eviction filed in the Burgh Court for every fifty-four people in the year 1886. To make matters worse, in 1911, the Housing (Scotland) Act shortened the notice period given to tenants before eviction.[29]

The stage was being set for conflict. Working-class people had often resisted unfair rents, but this came at a significant social cost. As mentioned above, character references and clean tick books were often prerequisites for entering into a ‘missive’ and failure to provide these could see a family relegated to the lodging house, the poorest single-end or to the street. Regardless of the risks, some would avoid their rent payments and disappear before their factor could visit to collect. The early twentieth century saw these actions supplanted by more boisterous and political acts of resistance; tenants began to refuse to leave their dwellings while in arrears, forcing their cases to be heard in the courts. Working-class institutions like the trades unions and the Labour Party incorporated housing issues into their purview, advocating for the introduction of a programme of municipally owned, high-standard housing as early as 1902. The issue became a mainstay of Scottish pre-war politics; the Labour Party’s fortunes, which had been stymied by the dominance of Home Rule for Ireland in political discourse, rapidly changed as they contributed more efforts on behalf of tenant’s rights and housing conditions in the urban realm. The disgusting, cramped and diseased conditions in which many, even the more fortunate, lived fostered a boiling anger which was only too glad to finally receive an outlet.[30]

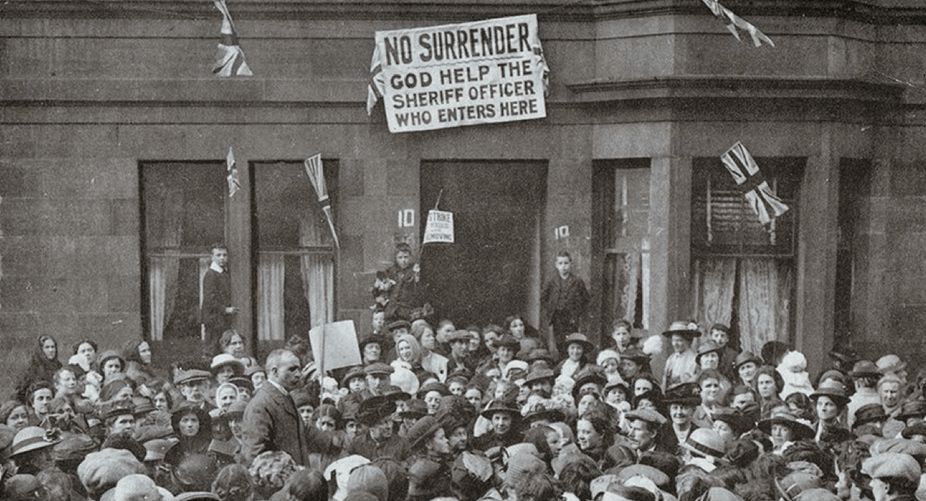

The situation would only be exacerbated by the First World War. As mass volunteering for the war effort left large numbers of vacancies in factories and other workplaces, urban areas were flooded with workers looking to take advantage of the need for labour in essential industries. This put significant pressure on the available housing, of which building had ceased for the duration of the war, and saw landlord’s asking prices for deposits and rent rise in order to capitalise on the situation. In addition to this, war conditions saw the prices of common commodities rise, cutting further into the budgets of the already-suffering working class. Many people were forced to lodge with a family already occupying a tenement house, easing the strain on both their finances but aggravating the dire, insanitary conditions that already plagued these homes. For thousands of families, this was the breaking point. In the spring and summer of 1915, under a campaign led by women’s groups like the Govan Women’s Housing Association and the Federation of Female Workers alongside the male dominated industrial unions and the Labour Party, masses of people in Glasgow and across Scotland began to withdraw their rent payments. Landlords, factors and other housing agents, coming to collect their rent, sequester property or serve notices of eviction were met with mobs who attacked them, humiliated them by covering them in eggs and flour and who would openly mock and shame them. Mass demonstrations took place, most notably in Glasgow, but also in other cities across the country, protesting for the introduction of rent controls for private rents, municipally-owned housing and the creation of tenant’s courts, where working-class tenants could settle disputes and state their case against their landlords. Though tenant’s courts would not appear, the struggles of the summer of 1915 were successful: the autumn saw the passing of the Rent Restrictions Act, placing for the first time limits on the increase in rent in the United Kingdom.[31]

So too were the strikers successful in persuading government of its responsibility to provide housing. From the Addison Act 1919 onwards, a programme of national housebuilding began, providing for the first time a municipal alternative to private renting. A series of four further Acts between 1923 and 1938 established subsidies for private rents and for slum clearances, among other reforms aimed at easing the pressure of the housing market on tenants and improving the urban cityscape.[32] McCrone and Elliot characterise these pieces of legislation as a ‘sacrifice’ of landlordism by the industrial interests that dominated central government; the actions of rent strikers and the involvement of workers’ organisations in their campaigns threatened to create a situation in which revolutionary spirit flourished, threatening the British state directly. Housing was not only the most politicised issue of this period, but also the most malleable and so intervening into the workings of the housing market made all the more sense to the industrial bourgeoisie who feared a campaign of industrial action or agitation for workers’ control of the economy.[33]

Devine marks the interwar housing legislation as a watershed for the construction and form of the Scottish townscape: no longer were tenements favoured, at least the type that was common in the preceding years, as the trend of low-rise flat blocks and semi-detached council housing, which would define the Scottish urban realm more and more throughout the century, was born.[34]Despite these significant gains on the part of tenant’s and the working poor, municipal housebuilding in the immediate inter-war years proved unsatisfactory. Of the 300,000 houses envisioned to be built in the first few years following the armistice, only 31,000 of those had been completed – 2,000 of which were in Scotland. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, with turbulent national politics and the onset of depression, various housebuilding schemes were attempted or re-attempted with varying degrees of success. Slum conditions continued to develop in older properties. Rent strikes continued to occur in this period, and although it was hoped that concessions toward rent controls and municipal housing would insulate industrial capital from the most radical elements of the growing communist and socialist movements, a general strike was called in 1926.[35]

Though small in number, the new housing schemes created between the wars did offer Scottish tenants – the lucky few – a marked improvement over life in the older areas of the cities. A primary benefit was the inclusion of more rooms; for the first time it was possible for many families to assign a separate bedroom for each child, allowing for much improved privacy and spatial use. However, this new privacy and form of living proved to be too sharp a change for some who missed the communal nature of living in a tenement block: the socialising which was necessary during the daily housework, the ability to rely on close neighbours to watch the children when needed and the familiar social spaces of the pubs, all of which were largely absent from the schemes. It was not unheard of for people who missed these attributes to return to their old neighbourhoods.[36]

Social class is omnipresent in the history of housing in Scotland. As much as it is the history of a housing type, it is the story of two classes whose fortunes increasingly diverged over the course of two centuries, with one gaining access to the higher echelons of Scottish society, exercising command over the form of their environment and reaping wealth unimaginable to their ancestors. The other forced into tight city blocks, bound by rigid social and economic mores, compelled to fight for even the most meagre reforms to be taken by those with power. Distance between the classes was also physical; increasingly, the Scottish city became rigidly divided into quarters occupied by the members of similar occupations, incomes and living conditions. Efforts to contain the worst filth, disease and poverty experienced by Victorian Scots were also tainted by class discrimination and interest. As we will see later in my research, the implications of these dynamics do not only concern the people of the squalid nineteenth century slums, but run vein-like through the history of Scottish housing into the present day.

[1] TM Devine, The Scottish Nation, (2006, Penguin, London) pp.123 – 155

[2] David Jones, ‘Living in One or Two Rooms in the Country’, in (ed.) Annette Carruthers, The Scottish Home (1996, National Museum of Scotland, Edinburgh) pp.37 – 57

[3] Ian D. Whyte, ‘Urbanisation in Early Modern Scotland: A Preliminary Analysis’, Journal of Scottish Historical Studies Vol 9 Issue 1 (1989) pp.26 – 29

[4] Ibid. pp.30 – 32

[5] Aaron M Allen, ‘Conquering the Suburbs: Politics and Work in Early Modern Edinburgh’, Urban Studies Vol. 37 Issue 3 pp.431 – 435

[6] Bob Harris, ‘Towns, improvement and cultural change in Georgian Scotland: the evidence of the Angus burghs 1760 – 1820’, Urban History Vol. 33 Iss. 2, pp.200 – 210

[7] TM Devine, ‘The merchant class of the larger Scottish towns in the later seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries’, in G. Gordon and B. Dicks (ed.) Scottish Urban History (1983, Aberdeen University Press, Aberdeen) pp.92 – 102

[8] Helen Clark, ‘Living in One or Two Rooms in the City’, in Annette Carruthers (ed.), The Scottish Home, (1996, National Museums of Scotland, Edinburgh) pp.59 – 61

[9] Ian Gow, The Scottish Interior

[10] These figures were calculated using information from a Glasgow City Council leaflet on demographics, available here: https://web.archive.org/web/20070703130648/http://www.glasgow.gov.uk/NR/rdonlyres/E3BE21DA-4D84-4CC4-9C02-2E526FDD9169/0/4population.pdf

[11] Enid Gauldie, Cruel Habitations: A History of Working Class Housing 1780 – 1918pp.84 – 85

[12] Edwin Chadwick, Report on the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population of Great Britain, (1843, W. Clowes and Son, London) p.42

[13] George Bell, Days and Nights in the Wynds of Edinburgh, (1849, Johnstone and Hunter, Edinburgh) p.31

[14] Ian Gow, The Scottish Interior: Georgian and Victorian Décor, (1992, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh) p.120, fig. 49b

[15] Helen Clark, ‘Living in One or Two Rooms in the City’, in Annette Carruthers (ed.) The Scottish Home (1996, National Museums of Scotland, Edinburgh) pp.59 – 82

[16] AA McLaren, ‘Class Formation and Class Fractions: The Aberdeen Bourgeoisie 1830 – 1850’, in G.Gordon and B. Dicks (ed) Scottish Urban History (1983, Aberdeen University Press, Aberdeen) pp.112 – 123

[17] D. McCrone and B. Elliot, ‘The Decline of Landlordism: property rights and relationships in Edinburgh’, in (ed.) Richard Roger, Scottish Housing in the Twentieth Century (1989, Leicester University Press, Leicester) pp.219 – 220

[18] Ibid. pp.219 – 220

[19] Richard Roger, ‘Crisis and Confrontation in Scottish Housing 1880 – 1914’, in Richard Roger (ed.) Scottish Housing in the Twentieth Century (1989, Leicester University Press, Leicester) pp.39 – 40

[20] TM Devine, The Scottish Nation (2006, Penguin, London) pp.329 – 331

[21] JG Robb, ‘Suburb and Slum in the Gorbals: Social and Residential Change 1800 – 1900’, in G.Gordon and B. Dicks (ed.), Scottish Urban History (1983, Aberdeen University Press, Aberdeen) pp.132 – 165

[22] CM Artherton, ‘The Development of the Middle Class Suburb: The West End of Glasgow’, Journal of Scottish Historical Studies Vol 11, Issue 1 (1991) pp.23 – 24

[23] TC Smout, A Century of the Scottish People (1986, Collins, London) p.32

[24] TM Devine, The Scottish Nation (2006, Penguin, London) p.341

[25] Ian Gow, The Scottish Interior: Georgian and Victorian Décor (1992, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh) pp.121 – 124, fig. 50a, 50b & 50c

[26] Ibid. pp.126 – 127

[27] Richard Roger, ‘Crisis and Confrontation in Scottish Housing 1880 – 1914’, in Richard Roger (ed.) Scottish Housing in the Twentieth Century (1989, Leicester University Press, Leicester) pp.33 – 39

[28] Ibid. pp. 26 – 30

[29] Ibid. pp. 41 – 42

[30] Joseph Melling, ‘Clydeside Rent Struggles and the Making of Labour Politics in Scotland’, in Richard Roger (ed.) Scottish Housing in the Twentieth Century (1989, Leicester University Press, Leicester) p.58 – 65

[31] Ibid. pp.65 – 70

[32] TC SMout, A Century of the Scottish People 1830 – 1950, (1986, Collins, London) p.52

[33] D. McCrone & B. Elliot, ‘The Decline of Landlordism: Property Rights and Relationships in Edinburgh’, in R. Rodger (ed) Scottish Housing in the Twentieth Century (1989, Leicester University Press, Leicester) pp.223 – 227

[34] TM Devine, The Scottish Nation, (2006, Penguin, London) p.347 – 348

[35] Joseph Melling, ‘Clydeside Rent Struggles and the Making of Labour Politics in Scotland’, in R. Rodger (ed.) Scottish Housing in the Twentieth Century (1989, Leicester University Press, Leicester) p.75

[36] Helen Clark, ‘Living in One or Two Rooms in the City’, in Annette Carruthers (ed), The Scottish Home (1996, National Museums of Scotland, Edinburgh) p.81 – 82

One thought on “Housing, Life, Consumption and Class in Modern Scotland”