Pilton is a housing scheme in the north-west of Edinburgh made up, originally, of four-in-a-block cottage-flats, three-storey tenements and semi-detached timber houses. Recently, modern private and mixed-residential developments have begun to spring up around the area, but the older housing forms continue to dominate the area. The scheme, or rather the two schemes of East and West Pilton, were built in stages throughout the 1930s and 1940s under several of the inter-war Housing Acts geared toward the clearance of slums and the rehousing of their residents. Sean Damer’s work on the inter-war council housing of Glasgow, where there existed a unique three-tier ‘league table’ of social housing standards, shows that the particular Act under which a scheme was built had significant social implications for the residents. The bottom two categories, ‘Intermediate’ and ‘Rehousing’, housed in the large part former slum-dwellers and as such came to possess the negative characterisations which plagued the inner-city tenements areas, exemplified by the surveillance of the Resident Factors and ‘Green Ladies’.[1] Being a slum-clearance scheme, my future research on Pilton will focus, partially, on the implications the system of council housebuilding under the various Acts had on the population there and across Edinburgh. However, today I would like to present something different – a ‘prehistory’ of the Pilton schemes. I use prehistory ironically, as Pilton’s history begins much further back than the construction of council houses and even the historical discussion presented here. Despite this, the popular perception of Pilton is that of a suburban, peripheral area connected to Edinburgh not by economic activity but primarily as a place of residence and a site of social problems and decline. This is in part down to a lack of attention paid to the area by historians as much as Edinburgh’s ‘City Fathers’ and housing planners of yore. My work here will show that Pilton’s identity as a working-class residential area marred by difficulties, which in any case is far from a complete understanding even presently, does not represent the full history of the area.

Before beginning, I would like to point out that this is not, by any means, a complete history of the area. This passage relies heavily on newspaper evidence, as a consequence of the coronavirus epidemic forcing the libraries and archives to stay closed, and as such is missing certain details that will be lurking in unreachable primary sources. What is presented here is constructed from as wide a range of sources as was available to me from open libraries, digitized archives and obscured .pdf documents.

Throughout the nineteenth century, what are now the estates of East and West Pilton, Drylaw, Granton and Muirhouse, were, in the main, large swathes of farmland and landed estates. Economic development, however, was not static; encroachment of industry and infrastructure into the farmland northwest of Edinburgh was a constant development throughout the period. If we compare two maps – Robert Kirkwood’s This Plan of Edinburgh and Its Environs (1817) and John Bartholomew’s Plan of Edinburgh and Leith with Suburbs from Ordinance and Actual Surveys (1880) – the extent of the change is obvious. The construction of Granton harbour and pier, extensive railway lines, bridges, scores of buildings and a network of roads set apart the area of the early and late nineteenth century. Industrial development remained on the periphery of Pilton until the next century, however its effects began to generate change in other settlements in the area. By 1845 the New Statistical Account saw fit to describe Granton as a “very populous district” on par with the two other main settlements in Cramond Parish, Davidson’s Mains and the village of Cramond itself. However, neither of the farms at Pilton are mentioned by name, though the farming tenantry in the parish are said to be a “very industrious and intelligent class of men”, and much of the discussion on housing is restricted to accounting for the many mansion houses and estates dotted around the area. Voiceless here are the agricultural workers, the majority population in the district at that time; the only indication the authors give of poorer residents in the area are statistics on the number of people claiming poor relief.[2]

The social life in Pilton at this period was influenced a great deal by the great agricultural developments of the previous century. Until some decades into the nineteenth century, most Scots were rural dwellers of some kind. In the Lowlands, a majority of people were ‘cottars’, landless workers whose home was provided to them along with a small plot in exchange for yearly labour on behalf of the tenant farmer, on whose rented land they lived. From the middle of the eighteenth century, this social structure began to come undone, being affected by the new modes of work that were introduced in line with ‘improved’ farming practices. Increasingly, labour was no longer seasonal, as it was realised that rotating crops increased farming output and, thus, the capital to be produced from farm work. Given that the cottars’ rights to their homes were not protected by law, they were cleared from the land, in cases violently, to make room for the planting of more crops and the introduction of waged year-round labour. Many cottars made their ways into the cities, crowded into the tenement blocks of the late Georgian period and into the ranks of the urban proletariat. Others, however, remained on the farms, though their relationship to the renting farmers was irreversibly changed, revolving now around capital where before it was access to land.[3] Farms surrounding large cities increasingly came to supply the growing industrial centres with food for both the growing urban population and industrial beasts of burden. Commonly, these farms grew turnips, potatoes, hay, oats and grass.[4] Newspaper evidence from throughout the nineteenth century shows that for the farms north-west of Edinburgh, this role was taken up readily, with turnips in particular a mainstay of the crops produced there.[5]

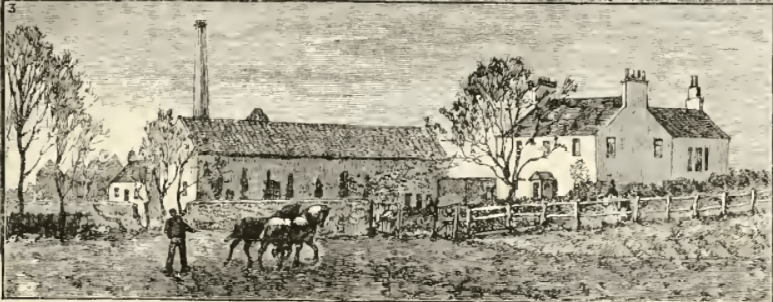

Imagery from Pilton in the nineteenth century offers a glimpse of the way of life brought there by ‘improvers’ and the agricultural revolution. East Pilton farm is depicted in an engraving volume three of James Grant’s Old and New Edinburgh, ostensibly a reproduction from an artwork produced early in the century. In it,the large farmhouse stands two-storeys tall and is accompanied by a longer one-storey house and a cottage further to the left; an illustration of the rural housing division as an extension of social rank.[6] The longer house in this engraving is likely the collective housing for farm hands, known as the ‘bothy’.

The bothy, distinct from the small Highland cottages of the same name, were the communal living spaces for agricultural labourers found on farm in the east of Scotland. In the west, a similar form of housing known as the ‘chaumers’ were provided, with the bothy differentiated by their possession of integrated cooking areas. Whereas, in the west, Lowland agricultural workers could eat food prepared for them in the farmhouse itself, farm servants in the east were expected to cook and consume their food in their separate lodgings. The buildings somewhat resembled barracks, with rows of beds on either side of the long building and a kist for each worker’s belongings to be held. These dwellings were not finely furnished and what extra furniture that appeared, beyond the beds, storage and eating surfaces, were usually old and unwanted wares from the farmer’s home. The dwellers of the bothy were, in the majority, unmarried men. For married workers, a cottage – like the one in the engraving – was usually provided. In the nineteenth century, these houses were typically of only one or two rooms. Much like their tenement-dwelling counterparts in the cities, rural cottagers had no choice but to assign multiple functions to their rooms, with the eating, bathing and sleeping commonly being done in the same space.[7] James Robb gave an account of these two types of dwellings in the Lothians in 1861. Of a two-storey bothy on one farm, Robb said:

“It has windows only on one side, but these are comparatively large and made to open. On the ground floor, there are two apartments … each apartment has one window. The larger … was occupied at the time of out visit by three Irishmen. Its furniture consisted of a table and three iron bedsteads, while a couple of short wooden forms did duty as seats. Two or three iron pots, and a basin of dirty water, stood under the table, while a mug and a few cups were upon it. On the hod beside the fireless grate … stood an ash-covered teapot … a blue woollen shirt covered what appeared to be a barrel in the corner … The blankets were certainly not snow-white, and there was a general appearance of dirt, and a close unwholesome smell in the place … The room up-stairs was occupied by one Highland girl. It was as large as the two below put together, and in summer is made to accommodate six or more persons. It has two windows, is airy and ceiled. There were in it three or four iron bedsteads, two tables, one of which supported a considerable display of crockery, and the other a Gaelic tract. A quantity of coal lay on the floor and a broken looking-glass hung on a nail by the side of the window.”[8]

Of a workers’ cottage, on a different farm, Robb said:

“The houses on this farm have mostly two rooms and a pantry; the floor of the kitchen a mixture of lime and ashes, that of the bedroom is boarded. They have, however, too little light and air. There are some new cottages here not yet occupied, which we inspected. They have a kitchen and parlour … the floor of the kitchen is laid neatly with tiles, the parlour is comfortably boarded. They have, besides, two small but airy and well-lighted bedrooms, a milk house, and a scullery with a sink for the dirty water. The houses are to be fitted up with iron bedsteads, grates and gas brackets … There will be gardens in the front of the houses, and all requisite conveniences in the back. The roofs are high, the rooms all lathed and plastered, and the windows are spacious and made to open … “[9]

What are, today, taken to be essential components of a home, such as a garden, energy supplies and inside toilets were certainly not universal and in many cases a rarity in rural workers’ homes in the Lothians of the nineteenth century. This variation in housing standards within the farm could also be found across the Lothians, with another farm visited by Robb showing older, more run-down cottage stocks. Further variation could be found in different industries, with particularly poor housing for the miners in Tranent, East Lothian, just ten miles from Pilton. Workers and their families there slept on piles of hay and shared their lodgings with animals whose droppings covered both the ground inside and outside of the houses.[10] Also akin to urban workers, farm servants tended to have large families, like that of Charles Bell, a worker on the East Pilton Farm from 1872 onward, who had nine surviving children of a total of fourteen in 1912.[11] This strain on space, even for those who lived away from the farm in houses of a potentially larger size, as the Bells did, is all too apparent.

In spite of this spatial poverty, there does exist some evidence that farm labourers in Pilton were not among the very poorest and could in some cases afford things that were out of reach for many slum-dwellers, urban proletarians and poorer rural workers. Indeed, Tom Devine’s examination of life for agricultural workers in the region during the years 1810 to 1840 finds that life there was relatively stable compared to elsewhere. In a period that saw rural labour risings in England and northern Scotland, along with food riots and the Radical War, the Lothians and south-east were peaceful. This is due in part to the preference for long-hires of six months to a year and the persistence of payment-in-kind into the nineteenth century, protecting agricultural workers there from the fluctuations of the market following the Napoleonic Wars.[12] James Robb’s account of the East Lothian farm workers’ pay shows that payment-in-kind – that is, payment in farm produce rather than cash money – was a popular method of remuneration even into the latter half of the nineteenth century. By his description, a farm worker there in 1861 could expect an annual payment-in-kind valued between £31 and £35, generally, and at highest, £41 15s.[13] Gradually, however, payment-in-kind and in perquisites began to cede ground to cash in the later nineteenth century so that by 1907 they were only accounting for 28 per cent of wages for farm workers in Scotland generally, and 15 per cent in the south-east in particular.[14]

While evidence could not be found of the exact wages at the farms in Pilton or the surrounding area, they do not seem to have fared much worse than their East Lothian counterparts. For example, Hugh Campbell, servant on the farm of West Pilton, brought a lawsuit against Sir James R Gibson Maitland of Barnton after Campbell had fallen into Craigleith Quarry. Campbell’s lawsuit alleged negligence and claimed that poorly maintained fencing was to blame for his forty-foot plunge into the quarry, where he lay all night.[15] Little is known of Campbell and it may be that he was of a higher grade than a simple labourer, but an individual worker raising the fees to pay a lawyer to bring a suit against a landowner suggests a certain amount of monetary or social capital. This case is, by any means, not a common one among the stories in the newspaper and it may be that Campbell was using his own savings to pay for the proceedings. There is evidence to support this theory, as in the case of John Thomas O’Donnell, a labourer on East Pilton farm, who was robbed of £27 10s of his savings by a man he had met while drinking in Edinburgh.[16] The ability to save money in these amounts attests to a better level of pay and cheaper costs of living for farm servants in Pilton than was available to workers in other sectors of the economy, and while Campbell’s lawsuit against a man significantly higher in social grade most likely failed, his actions speak toward a confidence in means not attributed to the poorest industrial inner-city residents. Further, newspaper stories of burglaries of Pilton farm labourers’ homes in the later nineteenth century, considering the presence of villas, farmhouses and mansions in the vicinity, perhaps point to a relatively decent material wealth among the workers there.[17]

Beyond their year-round labour, farmworkers in Pilton of the nineteenth century often took part in competitions in which they had the opportunity to show their prowess in their trades. For example, John Cleland, servant of Archibald F. Allen, the proprietor of East Pilton, placed in the top ten of a ploughing competition held at Mortonhall in February 1841.[18] Agricultural production extended out from the workplace and into the social lives of the servants of farmers. This stretching of work into play appears to have been exploited by the middle-classes to order and discipline their workers. This can be demonstrated by the organisation of an annual exhibition by the Cramond Parish Horticultural Societyin which prizes were awarded to farm servants for specimens of flowers, fruit and vegetables along with the conditions of the workers farmed lot adjoining their cottages.[19] Given the scrutiny of the workers’ houses here, it appears that these competitions were also a means through which the tenant farmers regulated the social and home lives of their workers, softly reinforcing the rural class system. Implicit bolstering of social rank can also be seen with George Stenhouse, owner of the farm at West Pilton: for his sixty servants in 1861, he threw a ‘sumptuous supper’ in the barn on the steading, decorated with evergreen plants. The number of servants itself is an indicator of the wealth of Mr Stenhouse, but it is interesting to observe that while, on the surface, the gesture was thankful, the workers were not dining inside the house but were still relegated to the buildings whose purpose was linked to the labour performed on the farm. This implicit paternalism seems to have gone unnoticed or was even accepted as normal by the workers; they thanked their boss in the lines of the local papers.[20]

Stenhouse appears often in the news of the period and it is clear from these occurrences that he was a wealthy man. He entrusted a neighbour with enough capital to purchase seven work horses, for example.[21] His house on West Pilton farm, in contrast with the labourer’s cottages, contained two ‘public rooms’, three bedrooms and an inside bathroom.[22] One of these ‘public rooms’ would have undoubtedly been a dining room. The importance of a dining room in middle-class homes, both urban and rural, had grown since the 1700s as the culture of consumption provided people of means with a way of expressing their class character and status in material objects. The importance of good china and the large tables, often made of expensive imported wood, was as much to do with exhibiting wealth as it was with entertaining guests.[23] In addition to his large farm at West Pilton, he was also the owner of land in Clermiston upon which he rented out a dairy farm, with enough room for up to 30 cattle.[24] Stenhouse’s farm had a very positive reputation in Edinburgh and was famed for its turnip and grass production, though it also grew wheat, beans and barley along with keeping horses and cattle. This reputation continued even past George’s death, as it was featured in an article in an 1892 edition of the North British Agriculturalist in which his widow states that she had continued to run the 170-acre farm in his absence. She also told the paper that Stenhouse’s connections with local Police Commissioners had helped to keep the farm afloat in its early years.[25]

Social as well as economic power can also be seen in Stenhouse’s one-time neighbour, Archibald Finnie Allen. Allen inhabited and ran the farm at East Pilton and also seems to have been considerably wealthy: an auction of his goods in December 1846 lists various work implements from carts to harnesses, myriad agricultural produce along with eight work horses, two ponies, four milk cows, twenty-eight swine and eighteen shots.[26] Allen was a founding member of the Scottish Mutual Insurance Association of Cattle and Horses, serving on the subcommittee which arranged the paperwork that dealt with its establishment.[27] He was also able to afford a game certificate, hunting being a notable pursuit of the nineteenth-century middle classes.[28] Allen was also signatory of a request for farmers to be in attendance at a debate on Corn Laws in Edinburgh’s Royal Exchange in March 1842.[29] Interest and involvement in local politics seems to have been a common thing among the notable farmers north-west of Edinburgh; in 1882, Peter Inglis, then the tenant farmer in East Pilton, was elected by the land and heritage owners as a Road Trustee for Crammond Parish.[30] Inglis was also made Vice-Chairman of the Crammond Parochial Board in 1886, serving under Henry Davidson, the tenant farmer at Muirhouse, in the latter’s role as the Chairman.[31] Involvement of the middling sorts in poor relief had long been an established practice, as they held much stronger connections to the local community than the lords and had colonised the ranks of the church since the previous century, and so it is typical that one might find the names of prominent farmers among the Parochial Boards.[32]

Being a tenant farmer in nineteenth-century Pilton, then, meant a lot more than running a business. It was a respectable middle-class profession through which great wealth could be had in the form of cash money but also in the form of social contacts and social control. The evidence above suggests that, whether in work or in receipt of poor relief, working-class people in Crammond Parish had to contend with the gaze of their social superiors extending into their private lives and their inner characters in a similar, though not identical, way to the urban poor.

Farmers, though, were not the whole of the middle-class that occupied the area in the nineteenth century. James Grant mentions, for example, that Wardie, east of Pilton, was “… studded by fine villas rich in gardens and teeming with fertility” by the time of his book’s publication in the late nineteenth century.[33] In the 1890s, Leith Burgh Council began planning the construction of a fever hospital at East Pilton, a six-acre patch of land lying on the East Pilton farm being chosen in October 1892.[34] Opposition to this plan from residents in the villas at Wardie was raised the following month in a special meeting of the Council, on the basis of concerns about a potential depreciation of the value of their homes if the building was to go ahead.[35] These concerns were resolutely ignored by the Leith Burgh Council and the construction proceeded on the site chosen. It was far from an easy process; controversy over the initial £36,000 cost and the realisation that the ground on which it was to be built required an extensive drainage system led to several changes to the architectural plans. Contractor delays held up the project for months, controversy arose over the issue of local governance of the Leith Council over a piece of Midlothian and even after the hospital had been built, a fire caused £100 worth of damages and two spires on the building had to be demolished and replaced due to irregularities.[36]

Locals’ concerns may have been ignored due to a snobbery held in Leith Burgh toward the more rural dwellers to their west. The system of competition between the Leith and Edinburgh Burghs produced a mutual antagonism between the two, with the latter holding the former in contempt as an inferior and peculiar town. Pilton, Muirhouse and the other north-western areas appear to have taken the brunt of Leith’s frustrations at their unfavourable comparisons with their larger neighbour, as they did during a meeting of the Leith Burgh Council on 29 January 1897. The drainage system for the East Pilton Hospital had burst, with raw sewage and medical waste pouring out onto the land and into the ocean at Leith. The Edinburgh bourgeoisie had relished their opportunity to taunt and mock their counterparts in Leith, leading to bruised egos and renewed bitterness in the town over a project that had already proven to be too much of a headache. When one member, a Councillor Waterstone, appear to agree with the criticism by complaining that his usual bathing grounds by the Chain Pier at Wardie had been polluted, another member openly mocked him by drawing a cartoon of him diving in and coming up covered in dung and other farm wastage – to the loud amusement of all except Waterstone.[37] The rural character of the area was a point of derision, despite the obvious status, wealth and influence many residents of the Pilton area held in the region.

Despite the mockery of the urban bourgeois, the rural character of Pilton and the surrounding area persisted for some time after the turn of the century. East and West Pilton, along with neighbouring farms, continued to produce turnips, grass and other agricultural products to be sold at public roups in the city.[38] Farming would continue to dominate the landscape in the area until the early 1930s, when the first sale of land for council housing occurred.[39] Horticulture and the celebration of prize specimens continued to play a role in social life, as shown by the holding of annual ‘Children’s Flower Services’ at Wardie United Free Church.[40] The appearance of the Bruce, Peebles and Company’s new engineering works in East Pilton brought the industrial development that had been slowly edging itself further west from Leith right to the farming community’s doorstep. This company would produce tramways for Hong Kong and, later, machines for the Brown Boveri company in Switzerland, and also provide employment for the area until its closure in 2005.[41]

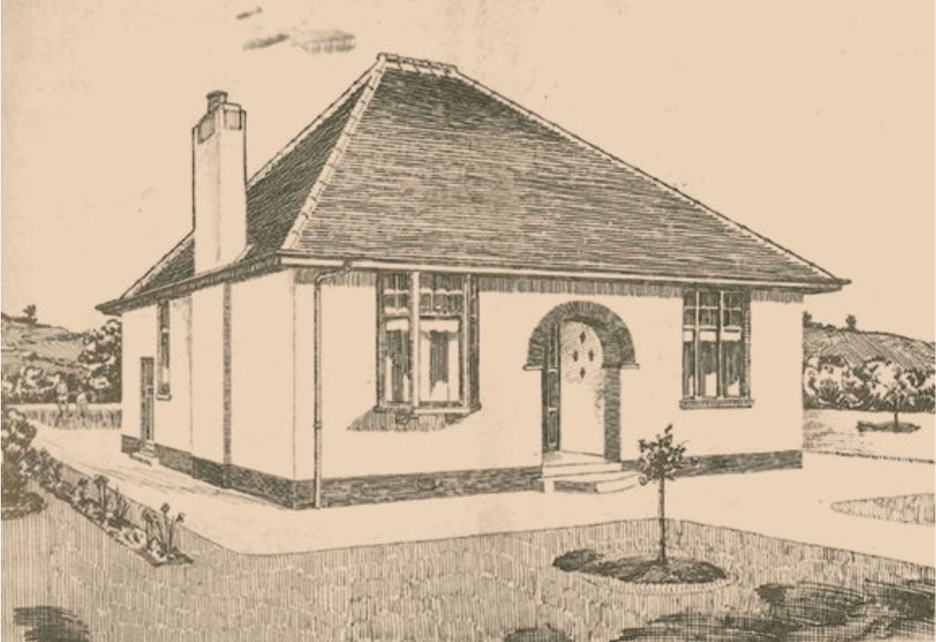

It was in the 1920s that the winds of change first came to Pilton. In 1922, as a result of persistently high post-war unemployment levels, Edinburgh Burgh Council began a £300,000 project of roadbuilding between Granton and Cramond with the belief that it would provide work both in its development and in future industrial development in the area. The possibility of housing or, as the council put it, “a new garden city by the sea” was also considered.[42] There was still a push to use the areas of Granton, Pilton and Muirhouse for the construction of factories and other works in the late 1920s; following the construction of a new electrical power station in Portobello, the Edinburgh Society for the Promotion of Trade produced a map in which north-west Edinburgh was marked as ‘schedule one’ readiness for industrial development.[43] It was not to be, however, as before even the council could begin building houses in the area, private developments began to spring up in Pilton. Despite the economic trouble which wracked the industrial workers of Scotland, clerical and other middle-class salaries grew in the inter-war years. In turn, this created a demand for new housing, which was met by a trend of private bungalow building in the outer limits of Scottish cities, helped also by a growth in car ownership and public transport provision.[44] Pilton was the site of one of these developments in the late 1920s and early 1930s; on Crew Road North, an example of these bungalows, complete with two bedrooms, a parlour, bathroom and scullery, was advertised with a yearly rent of £25 and a fue duty of £2 19s 6d, well out of reach for agricultural or industrial labourers.[45]

Despite these initial private developments, which continued to appear patchwork in the area throughout the 1930s, Pilton was not fated to become a land of bungalows and villas. In 1931, Edinburgh Corporation bought 150 acres of land, the first of many land acquisitions from the Duke of Buccleuch and the estates of Barnton, Sauchie and Bannockburn. Council housebuilding went rapidly underway, transforming the area and sweeping away the social life revolving around the production of agriculture. The name Pilton quickly became disassociated with high-quality turnips and Italian grass as the grey-harled tenements and stone cottage flats sprung up, replacing the farmers and their servants with an industrial population transferred from the slums of the Old Town and Southside.

The idea that Pilton’s history began with the construction of council houses, or that its importance in history is limited to its function as a housing scheme is patently untrue. While the drive for housing in the 1930s undeniably transformed the landscape and essentially shaped our conception of the area, its history and its social life up to the present day, Pilton before the scheme was host to a social life and system particular to a certain place in history. The rural class system there grew out of the changes in agricultural production in the eighteenth century and critically influenced the way that people related to one another. The agricultural worker in the Lothians, and demonstrably at Pilton, was not the lowest paid or worst-housed in the region, especially when weighed against the industrial workers in the city slums or the miners to the east, and appeared to enjoy stable wages and employment. However, they and their families, whether they realised it or not, had to contend with a paternalistic social order. This is perhaps embodied most strongly in the housing provided to them: lacking the space, the public rooms and, in many cases, the provision of an inside water source or wash closet that the tenant farmer could claim for himself. Pilton’s housing made solid the rural class system. The tenantry not only had more space to live, and to exude their wealth, but also the space to pursue political and economic ties with others of a similar standing. Their connections in the cities saw them act as insurance brokers and political agents, and their status in the countryside allowed them into the ranks of the church and onto the Parochial Boards. If the advent of council housing swept away the power of private landlords in the cities of Scotland, as Richard Roger shows, in Pilton it also done away with an entire system of rural social codes, production and economic relations.[46]

[1] Sean Damer, Scheming: A Social History of Glasgow Council Housing, 1919 – 1956 (2018, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh) pp.30 – 72

[2] New Statistical Account Vol 1 1845, pp.589 – 506

[3] TM Devine, The Scottish Nation (2006, Penguin, London) pp.123 – 155

[4] M. Stewart & F. Watson, ‘Land, the Landscape and People in the Nineteenth Century’, in Griffiths & Morton (ed.) A History of Everyday Life in Scotland, 1800 – 1900 (2010, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh) pp.23 – 29

[5] The Edinburgh Evening Courant Thurs 17 September 1868, p.2

[6] James Grant, Cassell’s Old and New Edinburgh Vol III, (1881, Cassell, Peter & Galpin, London) p.309

[7] David Jones, ‘Living in One or Two Rooms in the Country’, in Annette Carruthers (ed.) The Scottish Home (1996, National Museums of Scotland, Edinburgh) pp.40 – 52

[8] J Robb, The Cottage, the Bothy and the Kitchen (1861, William Blackwood & Sons, Edinburgh) pp.8 – 10

[9] J Robb, The Cottage, the Bothy and the Kitchen (1861, William Blackwood & Sons, Edinburgh) pp.3 – 4

[10] Enid Gauldie, Cruel Habitations: A History of Working-Class Housing 1780 – 1918 (1974, George Allen & Unwin, London) p.22

[11] Midlothian Advertiser Fri 05 January 1912, p.4

[12] TM Devine, ‘Social stability and agrarian change in the eastern lowlands of Scotland, 1810 – 1840’, Social History Vol.3 No.3 pp.331 – 337

[13] J Robb, The Cottage, the Bothy and the Kitchen (1861, William Blackwood & Sons, Edinburgh) p.11

[14] R. Anthony, ‘Farm servant vs agricultural labourer, 1870 – 1914: A Commentary on Howkins’, The Agricultural History Review Vol 43, No.1, p.62

[15] The Edinburgh Evening News Tues 29 November 1892, p.4

[16] Midlothian Advertiser Sat 01 December 1906, p.4

[17] The Scotsman Fri 10 May 1868, p.2

[18] The Witness Wed 03 March 1841 p.3

[19] The Scotsman Mon 09 August 1880 p.6

[20] The Scotsman Wed 30 January 1861 p.2

[21] The Scotsman Wed 24 April 1861 p.7

[22] The Scotsman Wed 12 July 1912, p.3

[23] Stana Nenadic, ‘Middle Rank Consumers and Domestic Culture in Edinburgh and Glasgow, 1720 – 1840’, Past and Present No.145, pp.142 – 143

[24] The Scotsman Thurs 19 March 1863 p.3

[25] The North British Agriculturalist Wed 24 August 1892, p.6

[26] The Scotsman Wed 23 December 1846, p.1

[27] The Scotsman Sat 18 January 1845, p.1

[28] The Caledonian Mercury Sat 31 August 1839, p.1

[29] The Caledonian Mercury Sat 26 March 1842 p.1

[30] The Scotsman Sat 16 September 1882, p.9

[31] The Scotsman Sat 04 September 1886, p.10

[32] RA Houston, ‘Poor Relief and the Dangerous and Criminally Insane in Scotland c.1740 – 1840’, Journal of Social History Vol 40, No. 2 pp.454 – 455

[33] James Grant, Cassell’s Old and New Edinburgh Vol III, (1881, Cassell, Peter & Galpin, London) p.306

[34] The Edinburgh Evening News Wed 26 October 1892, p.2

[35] The Edinburgh Evening News Fri 11 November 1892, p.3

[36] Information on the construction and decision making surrounding this project can be found in issues of The Scotsman, The Edinburgh Evening News, and other local papers between 1892 and 1899. These can be viewed if you have a subscription to the British Newspaper Archive; if not please contact me and I will provide my references if you’d like to write more on this topic.

[37] Musselburgh News Fri 19 January 1897, p.4

[38] The Scotsman Wed 02 September 1908, p.12

[39] The Scotsman Wed 02 September 1931, p.16

[40] Edinburgh Evening News Mon 11 July 1904, p.4

[41] Edinburgh Evening News Thurs 12 October 1905, p.2; The Scotsman Sat 9 November 1929, p.11

[42] The Scotsman Fri 13 October 1922, p.6

[43] Edinburgh Evening News Thurs 19 April 1929, p.6

[44] TM Devine, The Scottish Nation (2006, Penguin, London) pp. 348 – 349

[45] The Scotsman Sat 10 January 1931, p.3

[46] R. Rodger, ‘The Decline of Landlordism: property rights and relationships in Edinburgh’, in D. McCrone & B. Dicks (ed.), Scottish Housing in the Twentieth Century (1989, Leicester University Press, Leicester)

One thought on “Pilton: a prehistory”