Craigmillar and Niddrie are, today, two housing schemes joined at the hip, inseparable from each other physically, existing almost as one continual unit of suburban housing. The two communities are defined primarily by their ex-council housing stock, the oldest of which was built in 1930 in Niddrie in the form of three-storey tenements and cottage-flats but which grew to encompass developments of post-war flats, semi-detached housing and tower blocks. In recent years, new-built social housing has appeared as Niddrie and Craigmillar undergo redevelopment in gap-sites created by the demolition of some of the schemes’ original council housing. In spite of locals’ protestations to the contrary, the two communities have experienced a similar phenomenon to ‘Greater Pollok’ in Glasgow in which distinct schemes are rolled into one in the public’s consciousness. However, residents’ insistence in differentiating Niddrie and Craigmillar is in keeping with the area’s history; long before the construction of social housing, the area east of Edinburgh was far from uniform and was host to multiple landed estates, small villages, rural agriculture and industrial mining works. In this blog post I will cover the history of the area on which these two schemes stand before the construction of council housing in the nineteenth century and how the differences in employment, social status and lifestyle were expressed in the housing of the people there.

What is now the cohesive community units of Craigmillar and Niddrie was, in the nineteenth century, a collection of distinct areas defined by rural industries and agriculture, situated within the estates of the Baronetcies of Niddrie Marischal and Craigmillar. If we consult Robert Scott’s 1820 map of the area, we can see that there is no settlement noted as Craigmillar – though the ruins of Craigmillar Castle are clearly marked – rather there is a single village, Cairntows, where the modern housing estate lies today. Similarly, there is no single, cohesive town or village named Niddrie. Instead, a collection of settlements bearing that name appear on the site of the present-day community.

Examining art of the period can also allow for a glimpse at the character of this area of northern Liberton Parish of the 1800s. David Robert’s 1846 watercolour landscape painting of the Craigmillar ruins and the land surrounding it shows a vast swathe of arable land dotted only with a few country houses and cottages; in the right foreground two men are at work with cattle. Not visible here, however, are the collieries at Niddrie and Newcraighall.

Robert’s painting is a prime example of the romantic style that had been developing in Edinburgh from the latter half of the previous century, an art style which rose in tandem with the bourgeoisie and acted as a cultural mode of expression for that ascendant class. This style emphasised the rugged and picturesque, evoking the wild and accidental beauty of the country in its portrayals of the countryside; in poetry and literature, personal emotion and a sense of subjectivity in reaction to natural beauty were central themes.[1] The ruins of Craigmillar Castle were subject to both visual and literal romantic interpretations in the nineteenth century. Robert Gibb’s Craigmillar Castle from Dalkeith Road (c.1826) situates the castle in the background of a rural scene, populated by cattle, their gallant farming owner on horseback and two of his servants as they drive the livestock across a picturesque stream. A similar scene is portrayed in Anne Gibson Nasmyth’s View through the Gateway of Craigmillar Castle, Edinburgh, with Shephard and Animals. Both paintings fixate on the natural beauty in their depictions of the area, placing the splendour of the castle ruins within a traditional agricultural context.

Anne Gibson Nasmyth’s View Through the Gateway of Craigmillar Castle, Edinburgh, with Shephard and Animals

Robert Gibb’s Craigmillar Castle from Dalkeith Road (1826)

Poetry also subjected Craigmillar Castle to the notions of the Romantics; To Craigmillar Castle by ‘J.G.S’ in which the author mourns “how scenes of yore have long since passed away” and imagines the older way of life there before the times of improvement:

“Then I would picture, how on summers eve

The peasants round thy trusty walls would meet

How passing time they sweetly would deceive

How rig’rous youth would try th’ athletic feat

Not only these have seen thy happy days

But royal pomp beneath thy roof has dwelt”[2]

The loss of beauty and grandeur of this royal home was a recurring theme in Scottish poetry of the early nineteenth century. An elegy written by ‘an invalid in town’, in which Craigmillar Castle, Duddingston and the surrounding countryside are mentioned, appeared in an 1825 edition of The Scots Magazine. It read:

“Majestically rising, Arthur’s seat

In giant bulk uprears his lofty head;

Sees Royal Holyrood beneath his feet

Her glory gone, her ancient splendour fled!

And close beside, a cliff with front sublime,

Twin-born of Nature, like a sister stands

Whose venerable head, unhurt by Time

Is doom’d to fall by sacrilegious hands

Green shady woodlands wave on every side,

Where peeping forth gay rural villas shine;

Craigmillar, grey in age and ruin’d pride

Erewhile the theme of softer lays than mine:”

The author goes on to sentimentalise the “yellow harvest-clad” fields “ripening in the fruitful vale” along with “garden beauties beneath [their] feet”.[3] It is evident, then, that besides a longing for the past and mournfulness, the ruined castle and its grounds also inspired positive emotions, just as it did for James Hadden in his Scots language poem Bonny Craigmillar:

“By bonny Craigmillar wi’ Maggie

Fu’ faet flees the minutes awa’;

Tho wild be the scenery an’ craggie

Her love maks delight o’t a’

An’ tho we’re na lassie an’ laddie

To frisk like twa lammies in spring

An’ look for being mammie an’ daddie

We think nae o’ ony sic hing

‘Tis just to be happy thegither

An comfort to tak an’ to gi’e

That maks us so fond o’ ilk ither

An lichts up the lowe o’ our e’e

There’s nane o’s that can brag o’ our siller

But love needs nae eik tae it’s fire

The wild, healthy banks o’ Craigmillar

Wi’ Maggie is a’ I desire

Then come to my bosie, my dearie

And lat our minutes employ

We canna be poor nor be drearie

For love’s baith a treasure and joy

I look on Craigmillar’s fair palace

And thy humble cot on the muir

Wherein to my heart lives a solace

Yon castle can never procure.”[4]

These emotional responses provide us with important information about how the area was conceived by Scots in the earlier nineteenth century, to the sense of ‘place’ it held at the time. Artists and poets alike construed the area surrounding Craigmillar Castle as rugged, beautiful and virtuously rural in character. It is perhaps in part due to these romantic portrayals that the castle ruins attracted the attention of several notable visitors throughout the century. During a royal visit to Edinburgh in August of 1856, after lunching at Holyrood Palace, Queen Victoria and the rest of the Royal Family took a trip to visit Craigmillar.[5] Royal interest in the castle would persist throughout the century: Albert Edward, Prince of Wales, led a procession of Dukes, Earls and other nobles to the site during a trip to Edinburgh in 1899.[6] Its grandeur appealed also to the ranks of professionals; seventy members of the Edinburgh Architectural Association studied the castle’s interior and construction during an 1884 survey of the area’s architectural heritage, along with Peffermill and Prestonfield Houses.[7]

The castle ruins, however, were not simply an ornate embellishment to the Lothians’ natural landscape; throughout the nineteenth century, Craigmillar Castle and its grounds were used for myriad social and economic activities. Its purpose as a defensive keep was revived in 1804, when the First Regiment and Second Battalion, Second Regiment of the Royal Edinburgh Volunteers staged a “sham fight” in the medieval complex as a demonstration for the benefit of the public and for their commanders.[8] Newspaper advertisements also shows that the grounds of the castle were a popular site for the breeding and sale of horses.[9] Later in the century, the surrounding area was also home to deer nurseries.[10] However, its secluded location on a large country estate, surrounded by woodlands also made it attractive to criminals. The presence of deer and other animals belonging to the Gilmours, the landowners of the Craigmillar estate, inevitably attracted poachers to the castle, such as the chimney-sweepers William Lang and Colin Reid who were found hiding with a rifle on the estate in 1877 and fined £1 11s 6d.[11]

The castle was also the site of several cardsharping operations, whereby confidence tricksters would entice their victims into parting with their money via a rigged card game. It appears that this was a common occurrence throughout the mid-to-late nineteenth century: an 1858 newspaper article bemoaned the fact that “scarcely a week passes in which we do not hear that someone has been decoyed out to Craigmillar Castle, and there induced to part with some money, a watch or something valuable”, stating that the perpetrators often found their marks in Princes Street.[12] A detailed case of this scam was given in an 1869 edition of the Renfrewshire Independent. In Princes Street, a visiting Highlander was approached by a man calling himself MacFarlane, who invited the traveller for a carriage ride to Craigmillar Castle. Upon arrival, they met two men playing a game of cards and on MacFarlane’s insistence the young Highlander bet £2 of his own money and lost. MacFarlane, however, won £10 and encouraged the man to bet further. When it was revealed that the man had no more money to bet, and so no more money could be robbed from him by the fraudsters, he was sent back into town ostensibly to collect money from MacFarlane’s hotel room. Upon asking for his room at the hotel, the Highlander was arrested, being mistaken as a member of the gang. The police surmised that he was a victim and, after travelling around the Southside of the city, they were able to find and identify MacFarlane as a noted cardsharp by the name of “Church”. The article notes that no laws existed to punish the man, and so he was let go and the Highlander remained without his lost money.[13]

Notable and sometimes notorious, then, was the land surrounding Craigmillar Castle. However, the Craigmillar estate encompassed much more than the castle ruins, and the area which would make up the modern scheme also includes the estate of Niddrie Marischal. From newspaper advertisements of property being let on these lands, we can surmise the true size of the lots owned and fue’d out by the landed classes in these times. An 1821 notice shows four farms on the estate of Craigmillar ranging in size from 15 acres to 109 acres, and in location from the northern bounds of Liberton Parish to the villiage of Liberton itself.[14] A similar notice shows farms as large as 230 acres on the lands of Niddrie Marischal, grouped around the main manor house.[15] While I will be touching on the tenantry and farm servants living in the area in this post, I would like to turn first to the gentry. In my last blog post on Pilton little is mentioned of the landed classes there beyond the presence of their mansions; they appeared very much to be absentee landlords. In contrast, the gentry to the east of Edinburgh appeared to have involved themselves much more in the local social life there and were often mentioned in the newspapers as attendees at various gatherings of high society in the city.

For example, the Gilmours of Craigmillar and the Wauchopes of Niddrie Marischal were attendees of the “drawing room”, a ball in which notable women from around Edinburgh were presented, held by King George IV on his visit to Edinburgh in 1822. If their invitation to this exclusive gathering is not evidence enough of their status in Scottish society, then the details of what the women wore to the ball, published in the newspapers, might be. Mrs Little Gilmour is said to have worn a white tulle dress with satin, ornaments and pearls; Mrs Wauchope wore a dress decorated with feathers and diamonds.[16] The Gilmours also rubbed shoulders with Scotland’s other nobles: Walter James Little Gilmour attended the 1827 Edinburgh Races with the Earl of Caithness and Sir Walter Elliot.[17] This closeness to royalty was reciprocated by the landed families in the area; for Queen Victoria’s visit north in 1842, following a trail which would lead the royal party through the lands of Niddrie, Andrew Wauchope contracted a local joinery firm to build a “splendidly decorated triumphal arch” through which their carriages would pass.[18]

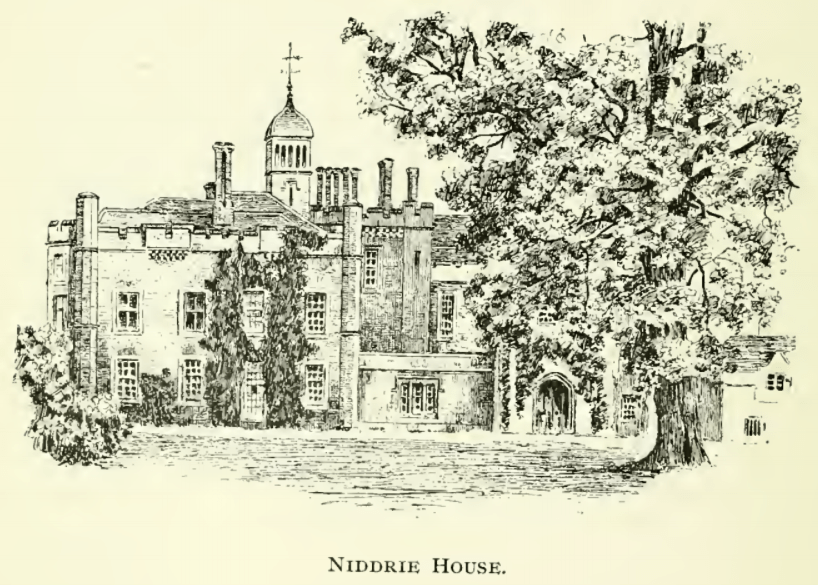

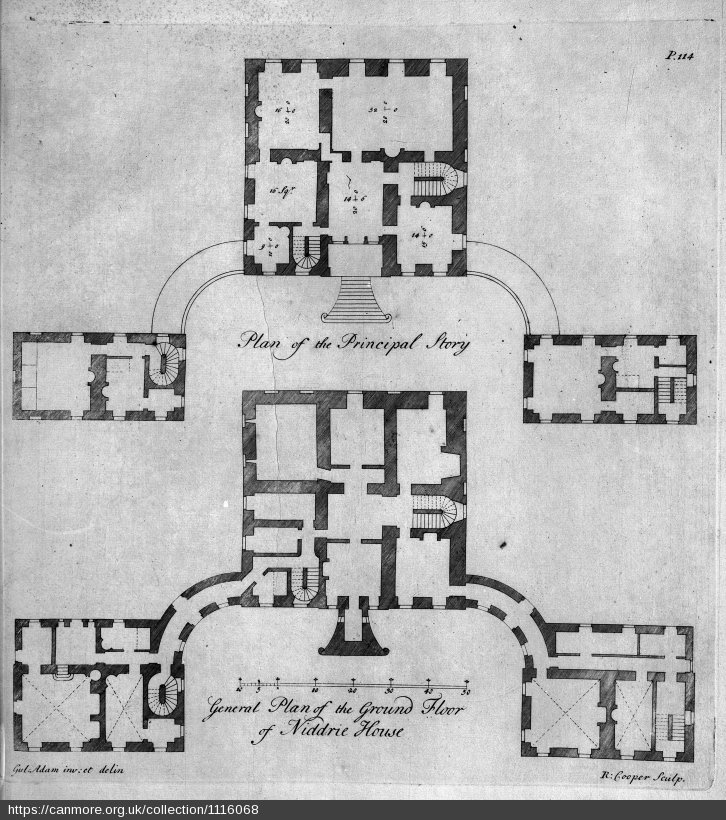

The wealth and elite social position of the gentry was reflected in the grand homes in which they inhabited. The splendour of their grounds is perhaps embodied most by Niddrie House, the Wauchope’s manor home. An engraving of the building and its setting appears in Tom Speedy’s 1892 work, Craigmillar and its Environs with Notes on the Topography, Natural History and Antiquities of the District. Speedy deems the grounds in which the home is set “beautifully and tastefully laid out”, and the design of the manor house itself seems designed purposefully to suggest a royal residence. Castle-like, the house is made up of several wings, one of which includes a large tower; visitors to the home had to pass through a large arching gate, presumably operated by a groundsman or guard, whose residence may have been the building in the far right of the engraving.[19]

The Wauchopes and Gilmours stood at the top of a paternal rural class structure. Directly below them were the renting farmers: rural businessmen who operated agricultural enterprises on the leased land from the gentry. Tenant farmers were men of status and wealth, deriving their existence from the money made by using the labour of agricultural workers to farm the plots of land they rented from the gentry. This powerful and economically fruitful social position as the middle-classes in the countryside was a relatively new phenomenon in Scottish history. While renting farmers had existed as a class in rural Scotland for centuries, holding land in exchange for the production of crops and labouring on behalf of their landlords, their transformation into rural businessmen had only begun in latter half of the eighteenth century. At that time, the desire of the landed classes to tap into the growing money economy saw the introduction of money rents, forcing renting farmers into the market economy and placing the onus of profitability onto their farms. What followed was a restructuring of the rural class system, decimating the cottars, the landless class eking out an existence in subsistence farming, and enclosing sections of arable land into large farms. The renting class were rewarded, however, for their support of these measures: the large farmhouses they came to live in were often newly-built for them by the gentry in return for their backing of these ‘improvement’ measures.[20] There existed, then, some economic collaboration between the gentry, the traditionally dominant class, and the new rural middle-classes whose economic power often outstripped that of their social superiors.

Despite this newfound economic power, social inferiority seems to have been accepted by the tenantry of Niddrie and Craigmaillar. In fact, much evidence from this group seems to support Antonio Gramsci’s notion that the British bourgeoisie, in stark contrast to the French, saw the gentry and aristocracy not as competition for hegemony but rather as the cultural and intellectual counterpart to their economically dominant class position.[21] The Niddrie and Craigmillar farmers often paid tribute to their landlords and their landlord’s peers. For example, names of the tenant farmers at Niddrie Mains and Niddrie Mill, for example, appear on the list of stewards for an honorary dinner thrown in February 1835 for the Duke of Buccluech in the Assembly Rooms on George Street in Edinburgh.[22] The tenantry also appeared to emulate the gentry in their social and cultural pursuits. For example, Bentham Douglas, the tenant farmer in Cairntows became a member of the Royal Highland and Agricultural Society in 1858, whose membership included the gentry at Craigmillar, in a ceremony overseen by the Duke of Buccleuch.[23] Further, in a list of contributors to the Royal Patriotic Fund – a charity set up to assist the widows and orphans of fighters in the Crimean War – appear the names of several tenant farmers from the Niddrie and Craigmillar areas, along with Walter James Little Gilmour.[24]

Much like the tenantry in Pilton, the farmers in Craigmillar and Niddrie also organised to protect their own class interests. During an 1865 outbreak of Rinderpest, a disease which causes necrosis and eventual death in cattle, the Edinburgh Dairymen’s Mutual Protection Association was established to ensure its members against any loss of cattle to the virus and to co-ordinate preventative action with the town council. Among its founders were Bentham Douglas of Cairntows, also elected Treasurer, and John Mylne of Niddrie Mains farm.[25] Six months later, these men were also present when the Association decided to wind down its operations due to their inability to prevent the spread of the disease, voting instead to destroy the infected cattle and butcher the healthy specimens in order to sell their meat.[26] Also akin to their counterparts in Pilton, the farmers to the east of Edinburgh also shored up their class position through involvement in politics; William Harper of Cairntows was listed as one of William Ramsay’s, Conservative Member for Midlothian, ‘loyal servants’ (as much a display of class collaboration as it was a sign of independent class action).[27] Similarly, Robert Young, of South Niddrie Farm and Niddrie Miln, signalled his intention to support a Conservative candidate in Linlithgowshire, where he was an elector.[28] Middle-class political actions were also evident later in the century, with the establishment of a branch of the Conservative Party-aligned Primrose League in Craigmillar.[29] Members of the renting farming class, alongside delegates from the Ploughman’s Union, were present at a meeting of the Midlothian Liberal Association in Niddrie Mains schoolhouse in May 1893.[30]

The involvement of the middle-classes in political behaviour appears to have instilled in them a sense of parliamentary procedure which was extended even to, ostensibly, non-political groups. For example, at a meeting of the Niddrie Bowling Club in October 1897, attended by several local councillors and middle-class professionals residing in the area, the membership paid respect to both the Colonel Andrew Wauchope and to the Niddrie and Benhar Coal Company. The proceedings were superficially legislative, revolving around the reception of reports and votes on the approval of measures.[31] This political culture would endure in middle-class communities even in wildly different contexts. For example, similar behaviour is found in Glasgow’s elite Mosspark council estate, populated in the main by urban professionals and businessmen, in the 1920s and 1930s with regard to community organisations such as the local tenant’s association.[32]

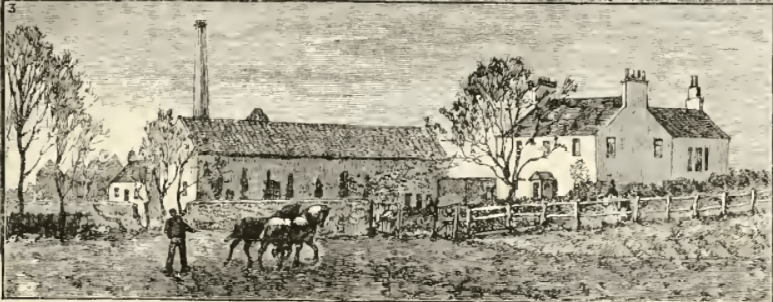

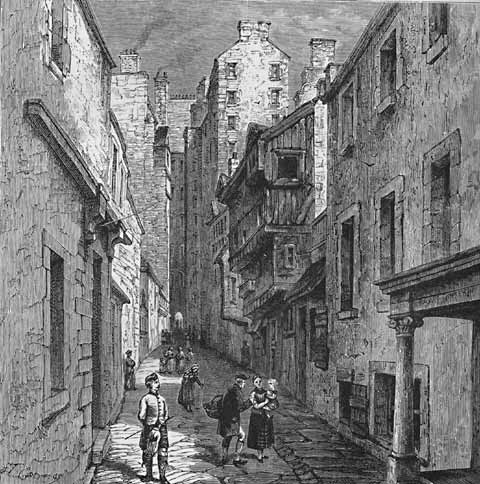

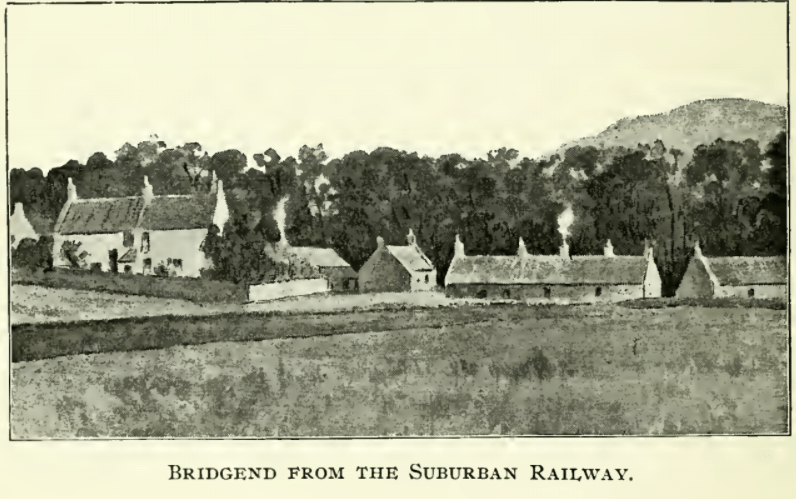

As mentioned, the homes of these renting farmers were substantial in size and offered the rural middle classes a living space with rooms of specialised function. That is to say that each room served a differing function of home life. This is common to modern homes, with separate kitchens, bedrooms, living rooms and toilets, but this was far from guaranteed for most people living in the nineteenth century. Farmer’s homes often had enough space for considerable decoration and were often furnished with expensive dining tables and other fashionable commodities that signalled the wealth of this ascendant social group. The renting class homes of Craigmillar and Niddrie were certainly large; the house at Niddrie Mill, beyond the rooms in the house, possessed a granary, bakehouse, shop, stable and attached garden.[33] An engraving of the farmhouse at Bridgend, now an incorporated part of the Craigmillar scheme, appears in Tom Speedy’s account of Craigmillar. In it we can see the housing for the middle-class and working-class workers side-by-side. The row-cottages reserved for labourers are fairly uniform, each containing only one floor, one door and apparently no windows. This is contrasted with the large, two storey farmhouse which possessed multiple windows and chimneys, signalling a diverse set of rooms of differing function, along with a large and walled-off garden to the rear.[34] It was possible, then, for the middle-classes to enjoy not only a great deal more indoor space, but also a significant amount of outdoor recreational space as well.

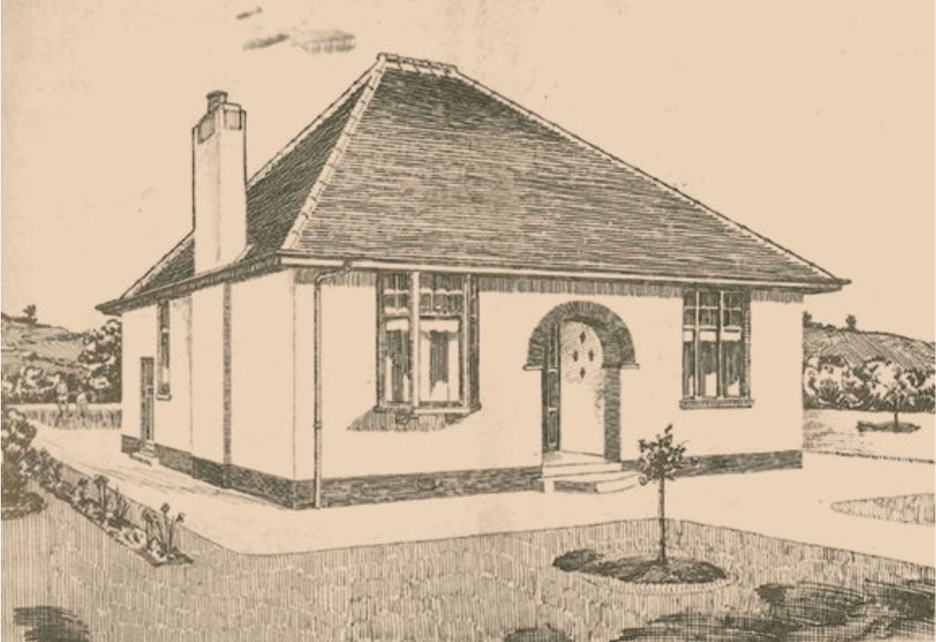

However, again as with Pilton, the middle classes in the area were not exclusively farmers. In the village of Duddingston, to the north of Craigmillar, several houses were let exclusively to middle-class people. For example, an 1804 advertisement for property being fued out by the Marquess of Abercorn, lists the schoolmaster’s willingness to teach children of a “better rank” privately and so “keeping them unmixed with the children of the labouring people”, alongside a view of a local manor house, the situation of the property near to Arthur’s Seat and the access to the farmer’s market in the village, as benefits of living there.[35] Another, from 1813, for a three-storey house in the settlement, complete with office space and a garden, declares the property to be fit for a “genteel family”.[36] Further, later in the century, a letter to the editor of the Daily Review arguing in favour of expansion the road from Cairntows to Duddingston “will soon be studded with fine villas”, a common period style of detached home for the well-off middle classes.[37] These examples of spacious housing, within easy reach of the city but set in the picturesque countryside, were likely occupied by commuting professionals.

The nineteenth-century working classes of Niddrie and Craigmillar were, similarly, not a monolithic bunch. Whereas in some areas, like Pilton, where agriculture appeared to be the dominant form of business and production, Craigmillar and Niddrie hosted several sites of both primary and secondary industries alongside farming. Varying modes of production, in turn, meant a varying social life and conditions. For the farm labourers at Pilton, though their families were often large and their houses composed of two rooms at most, evidence was found that their earning power may have been stronger and more stable than in other industries of the period. What was absent, however, was an account of the consequences faced by the workers and their families if this earning power was lost. An instance of this can be found among newspaper evidence regarding a worker from the Craigmillar area. Cairntows, like many of the other farms surrounding Edinburgh and indeed other cities and towns across Scotland, specialised in growing turnips, grass and other produce destined for the city markets as fuel for both industrial worker and workhorse.[38] In 1844, Alexander Robertson having finished his duties as a ‘servant’ to William Harper, then the proprietor, came off his horse in a riding accident on his way home from the farm. His horse appeared at his cottage without him, and his wife later found her husband lying dead from his injuries. He left behind not only his wife, but also an offspring of nine children.[39] The consequences of the loss of the breadwinner for this family were severe. Suddenly, the family of ten were now reliant on the goodwill of strangers; calls for donations to the deceased’s family were published in local papers.[40] This story underlines the precarity at which most families existed, dependant on the sole income source of the male breadwinner. The loss of a father or husband, given the size of families at the time, was often the beginning of a fall into destitution for working-class people.

Like their counterparts in Pilton, agricultural workers were subjected to a paternalistic oversight by their social superiors. In the case of Pilton, competitions were held in which both the workers’ skill in their trade and the conditions in which they kept their small gardens were scrutinised by a team of judges made up of the renting class bosses. In Niddrie and Craigmillar, similar processes of social conditioning were at hand. One David Stewart, a gardener for the Gilmour’s of Craigmillar, won several prizes for his skill in producing specimens of fruit and vegetable, including a first place for his Savoy Cabbages at an October 1829 meeting of the North British Agricultural Society.[41] Bentham Douglas, the above mentioned proprietor of Cairntows, acted as a judge for a competition held by the Currie Ploughing Society in January 1866. At this particular competition, awards were given to the man who produced the best ploughing job, but a special prize was reserved for the man who had stayed with his “master” the longest.[42] This tacit reinforcement of class power and the expansion of work into leisure time demonstrates the extent to which job and social life were intermixed for nineteenth century agricultural workers, reinforcing their identity primarily as an extension of their economic function.

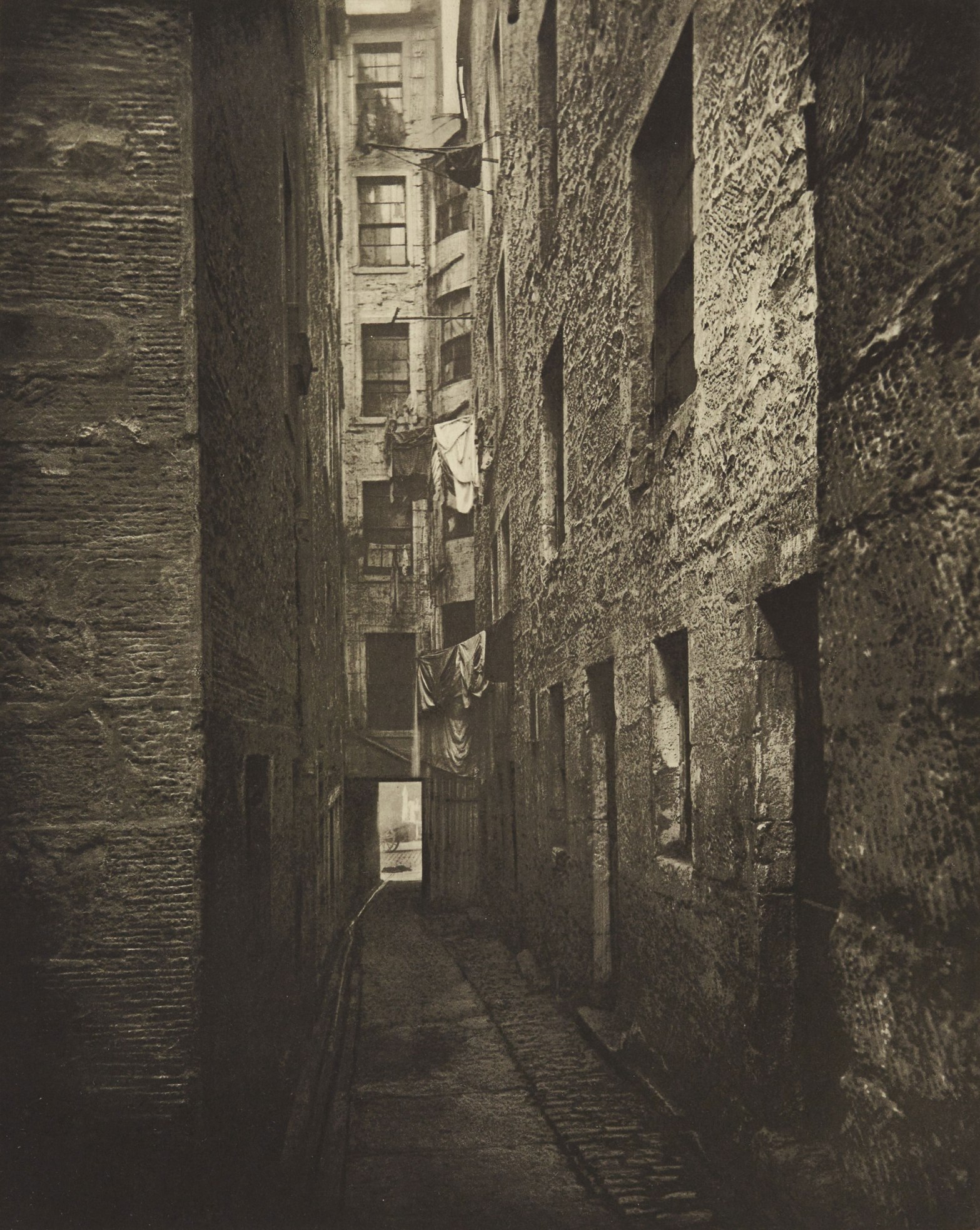

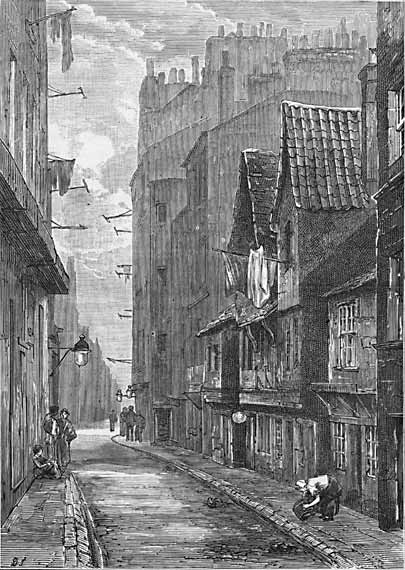

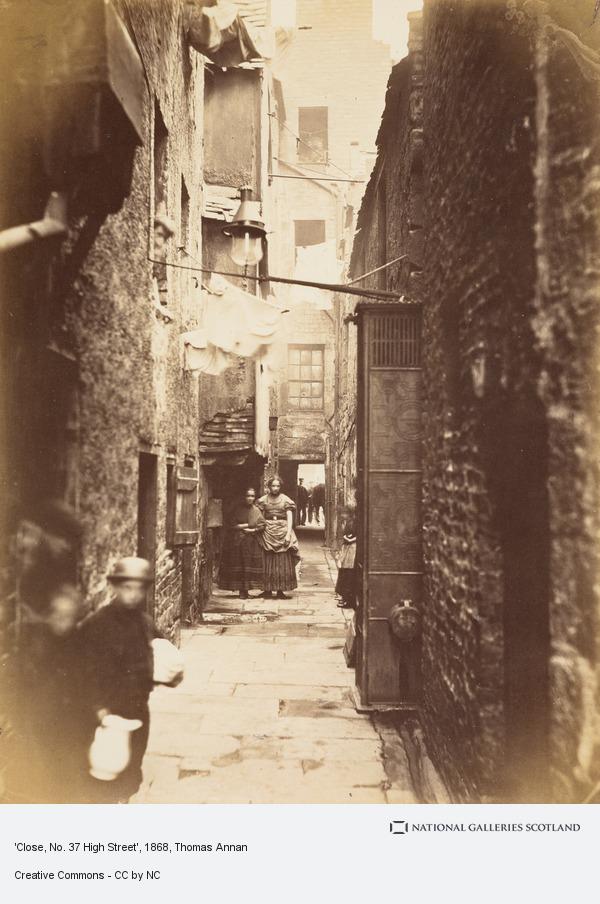

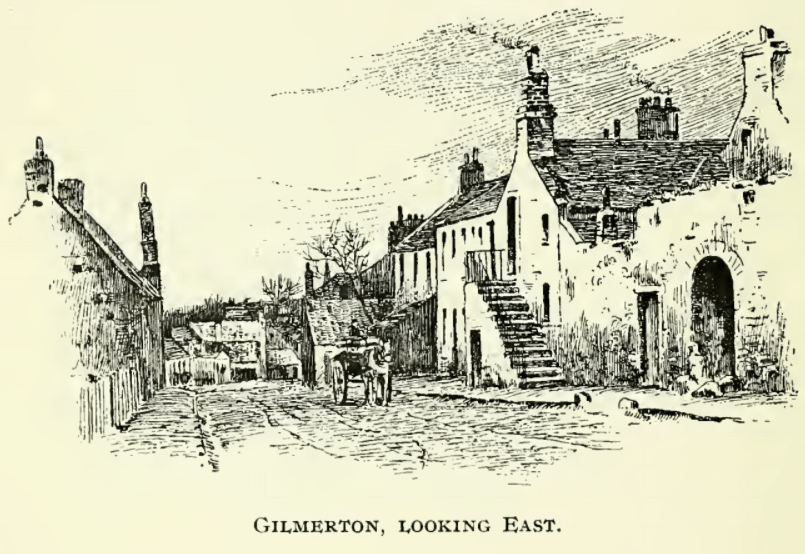

Housing for these agricultural workers was often provided for them as a part of their employment and, in the Lothians, often came in the form of a cottage or, for the unmarried, of a communal bothy. A discussion on the conditions and relations of these agricultural dwellings can be found in my previous blog, but an example of these houses in the Craigmillar and Niddrie areas can also be found above, in the engraving of Birdgend farm. However, an example of the conditions suffered by those in other industries is offered in the form of an engraving and description of the village of Gilmerton, again in Tom Speedy’s book. Though Gilmerton is not within our area of study, it certainly was linked to the area both through occupying space on the Craigmillar estate and through connections to the extensive mining works at Niddrie. From the engraving we can see, much like the farming communities in the Lothians, that the cottage appears to be the prevailing form of housing for those employed in other industries.

Speedy notes that the inhabitants of Gilmerton were understood to be lower-class and carried with them a reputation for violence and disorder. The inhabitants of Gilmerton were closely connected to the local mining industry, working in the majority as carters of goods from the mines through to the city. Some were also miners themselves; Speedy mentions that Gilmerton House, the local manor, was “rapidly losing its ancient character” due to its use then as housing for pit workers.[43] Ascribing a deleterious effect to these people betrays a certain disregard for the mining employees in the author, one which appears almost universal in accounts of the area at the time. Class discrimination was as present in the countryside as it was in the cities; for example, when in 1878 the farm in Little France caught fire and burned much of the master’s produce, suspicions immediately fell to local vagrants.[44] Discrimination was also practised through the erasure of working-class experience. In the above-mentioned characterisations of the Niddrie and Craigmillar area there is scant mention of the rural industries and the employees that worked them. This is despite a large stone quarry being located on the grounds of the Craigmillar estate, having existing from at least the first decade of the nineteenth century.[45] Another example can be found in a newspaper account of a writer’s walk through the Midlothian countryside, in which they emphasised the local manorial houses, fields and natural landmarks. Small mentions are made of railways and breweries, but in the main working-class activity and labour are ignored in these characterisations.[46]

Coal mining, however, appears more often in historical literature from the area. Like those working on farms in the region, many of the miners in the collieries of the Lothians had their houses provided for them by their employer. Even further, the social control mechanisms at work in the farms appear to have been present also in the mining communities; an 1875 article discussing the conditions of miner’s homes described the workers there as “a pacific, strike-disliking class of men” whose “employers exercise the paternal rather than the autocratic rule” of which the provision of houses was central. The article detailed the conditions of these houses, being generally of a cottage with a room and kitchen with sanded or stone floors and, in some cases decorated with plants, prints, engravings and cultivated flowers. The keeping of pet birds appears to have been popular with the miners, the author attesting to finding one home with as many as six cages in its ‘sitting room’. The author assessed these houses as having a “a certain air of cleanliness and almost of warmth” in character. Not all employees, however, were provided with homes. Many of the two thousand miners in the Niddrie area resided in separately rented houses, which could vary drastically in their qualities. Of miner’s houses in Adam’s Row, near to the main village of Niddrie, the following was said:

“… no ashpit is erected and the village is in a very dirty state, the roadway in front and the garden ground behind being alike untidy. There is not a closet in the place, but a deposit of bricks near the end of the long row is the forerunner, I am told, of such outhouses. For small room and kitchen houses the rent is 5s a month, and for single apartments 3s 4d a month. They are poor houses, but not positively unhealthy. Two wells give a never-failing supply of good spring water.”

Miners and those whose employment was linked to the collieries at Niddrie and Newcraighall, such as workers for the North British Railway, occupied houses in the village of Millerhill, where the landlord was a member of the Wauchope family. The houses here were of poor condition, older construction and were liable to dampness. Again, these houses were cottages of one or two rooms, the inclusion of the second room raising the rent from 6d to 10d per week. Two wells supplied the drinking and cleaning water for the two rows of cottages; there were only ‘closets’, outhouses, for one of the rows.[47]

Housing was often not only tied to work through its provision by the coal masters and landlords, but also physically close to work sites as well. Several of the houses in the village of Niddrie were close to the ‘Joppa’ seam which ran through the settlement and which had been worked up until the late nineteenth century.[48] The closeness of dwellings to workplaces was perhaps not accidental and ostensibly was a matter of convenience for both the workers and employers. Living as a miner in a mining village, socialising with other miners or those connected to the trade and watching the mine being worked, breathing in coal dust and listening to the operations go on even while off shift must have had a profound effect on the way the miners saw themselves and each other. This building of an identity around labour which was dangerous, difficult, and unrewarding (a quality perhaps best shown by the paltry houses provided by the company) no doubt was a significant force in the process of unionisation. Recent oral history work by Ewan Gibbs has demonstrated that these deep connections between mining as an employment form and the settlements which grew around pits continued to strongly influence the identity and social life of the residents of these settlements up to and beyond large-scale pit closures in the 1980s.[49] The shared suffering of the community was strong motivator in creating a class and sectoral identity which would endure for over a hundred years. The miners in Niddrie and across the Lothians organised to campaign for better conditions in their life and social work through the creation of trade unions. The Mid and East Lothian Miner’s Association (MELMA) was the organ through which the miners in places like Niddrie, Newcraighall, Tranent and Danderhall expressed their class identity and fought against the power of their ‘masters’ in the later nineteenth century.

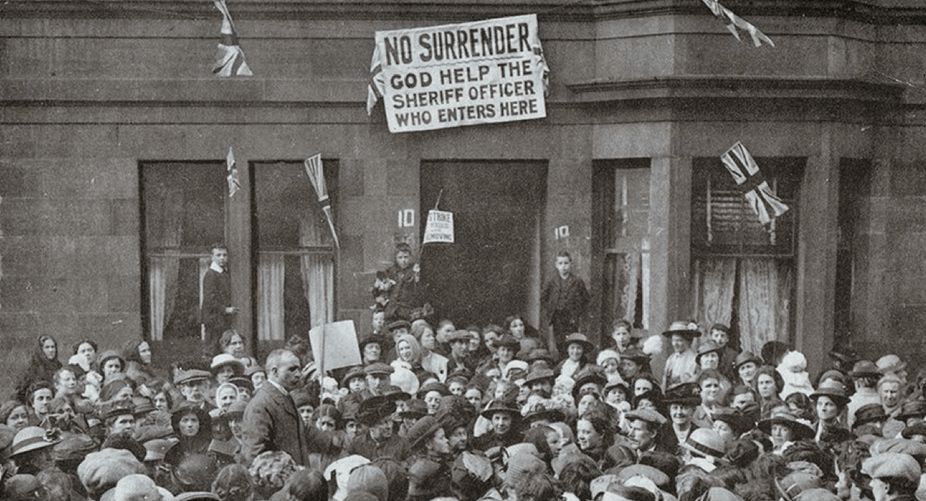

Though strikes, industrial action and unionisation had been attempted in the decades previous, the miners at Niddrie did not formally join MELMA until 1889, where they met on a grass pitch in Newcraighall and held a vote on the issue.[50] MELMA was involved in activities beyond the scope of the Niddrie mines and even beyond the Lothians. For example, in 1892, a ‘miner’s agent’ from Niddrie told the Edinburgh Evening News that the union intended to meet with William Gladstone, then the Prime Minister, during a forthcoming trip of his to Edinburgh, in order to discuss their campaign for an eight-hour work day.[51] Against the above charge of strike-weariness, the Mid and East Lothian miners voted to continue with a strike on 17 October 1894 where other Scottish unions had voted to go back to work, receiving continued support from the Miner’s Federation of Great Britain. However, only five days later the strike came to a halt as the mine bosses began evictions of workers from company houses.[52] This tactic was a common one for mine owners of this period: the minutes of the MELMA up to 1918 contain several mentions of pit bosses utilising their ownership of the miner’s houses to break up strikes and punish individual workers. To the miners, this practice was known as “victimisation”, a broad term which included any action against individual miners for their participation in strikes or other union activity. However, due to the strong connections between housing and workplace in Niddrie, its usage there embodies the understanding of these workers of this relationship, and that an attack on one had devastating consequences for both. Further, it betrays the notion that these miners saw their homes in emotional as much as material terms, placing these often-incommodious miner’s dwellings firmly into the “moral economy”. This perspective on housing would become an important prerequisite for the housing actions carried out during the First World War and beyond, helping to usher in the era of council housing and inspire continued action throughout the interwar period and beyond.[53]

Housing, then, was a central cause in the struggle for better conditions for the Lothian’s miners. The importance afforded to housing is shown in the organisational rules of MELMA: if a particular colliery had what was considered a high proportion of men residing in company houses, they were allowed more than one delegate to sit on the board of the organisation. For this reason, the Niddrie pits had two representatives on the governing body.[54] The miner’s union also sought to support men successfully “victimised” by their employers with regards to housing. In 1895 two such members were given cash payments to furnish their moving to a new home: Andrew Cunningham was given £1 after his eviction and firing by the Niddrie bosses; two weeks strike pay was also given to an Alexander Roger to facilitate his moving on from housing at the Niddrie colliery to the Polton colliery in Bonnyrigg.[55] The centrality of housing to the miner’s activities continued well into the twentieth century and the men of MELMA were involved in the housing struggles of the First World War. For example, during the rent strike of 1915, the union sent two delegates, including its president, to the Glasgow Labour Housing Committee’s Scottish National Conference on Housing, alongside 326 other unions, cooperatives and guilds.[56] This relationship with the Labour party seems only to have to strengthened over the years as the housing question gained national attention; on the 5th of January 1918, MELMA adopted a resolution to attend and vote on issues related to housing at a conference in Glasgow aimed at informing Labour Party policy.[57]

The history of Craigmillar and Niddrie certainly gives credence to local’s insistence that the two areas should be considered as separate and unique places. Craigmillar, to the west, was the site of farmland, a quarry and breweries. In Niddrie, coal mining was the dominant industry though farmland also occupied what is now parts of the modern scheme. Unfortunately, due to current events, exploration of the various industries in this area has been limited to what is available online which, though detailed in some respects, has sadly left out a lot of information about the quarrying and breweries. Nonetheless, we can see clearly that a rural class system was in full operation in Craigmillar and Niddrie in the nineteenth century and it affected the social and work life of everyone residing there. Whether a miner in Niddrie or a farm servant in Cairntows, the systems of production borne out of the later years of the previous century shaped and influenced one’s everyday experience. No where else was this as apparent as it was in the housing a person occupied. Wealth and status endowed the gentry and the renting farmers more space and so a more comfortable living, where there workers were left with inadequate homes of one or two rooms and often without suitable washing facilities. This class structure had an attendant ideology which, through both active and passive discrimination, denied the rural working classes representation in artistic, poetic and descriptive depictions of their home region. At work, especially in the agricultural sector, this ideology was tacitly enforced through worker’s participation in competitions which allowed their bosses to police their working skills and loyalty to their craft. However, the conditions at both home and work elsewhere, notably in mining, led the workers there to band together into unions to resist the power of their superiors.

[1] Nick Prior, ‘Edinburgh, Romanticism and the National Gallery of Scotland’, Urban History Vol.22 No.2 pp.210 – 215

[2] The Scots Magazine 01 November 1808, p.48

[3] The Scots Magazine 01 February 1825, pp.72 – 75

[4] Stonehaven Journal 08 October 1850, p.7

[5] Caledonian Mercury 30 August 1856, p.3

[6] St Andrews Citizen 15 July 1899, p.2

[7] Portobello Advertiser 19 April 1884, p.3

[8] Caledonian Mercury 27 February 1804, p.3

[9] Edinburgh Evening Courant 26 April 1828, p.1; ibid 20 December 1828, p.1

[10] Dundee Evening Telegraph Sat 19 December 1891, p.5

[11] Edinburgh Evening News 11 December 1877, p.2

[12] Stirling Observer 13 May 1858, p.3

[13] Renfrewshire Advertiser Sat 06 June 1869, p.5

[14] Caledonian Mercury 16 April 1821, p.1

[15] Caledonian Mercury 12 August 1822, p.1

[16] Caledonian Mercury 22 August 1822 pp.2-3

[17] Caledonian Mercury 27 June 1827, p.3

[18] The Witness 21 September 1842, p.3

[19] Tom Speedy, Craigmillar and its Environs with Notes on the Topography, Natural History and Antiquities of the District (1892, George Lewis & Son, Selkirk) pp.218 – 222

[20] Christopher A. Whatley, The Industrial Revolution in Scotland (1997, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge) pp.55 – 58

[21] Antonio Gramsci, ‘The different position of urban and rural-type intellectuals’, in Quinton Hoare & G.N. Smith (ed.), Selections From the Prison Notebooks of Antonio Gramsci (1971, Lawrence and Wishart, London) p.18

[22] The Scotsman 07 February 1835, p.1

[23] Edinburgh Evening Courant 14 January 1858, p.2

[24] The Scotsman 17 January 1855, p.1

[25] Caledonian Mercury 31 August 1865, p.1

[26] Daily Review 01 February 1866, p.2

[27] Caledonian Mercury 13 June 1839, p.1

[28] The Scotsman 15 August 1832, p.1

[29] Edinburgh Evening News 13 April 1892, p.2

[30] Mid-Lothian Journal 12 May 1893, p.6

[31] Musselburgh News 15 October 1897, p.3

[32] Sean Damer, Scheming: A social history of Glasgow council housing, 1919 – 1956 (2018, Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh)pp.17 – 23

[33] The Witness 15 February 1840, p.1

[34] Tom Speedy, Craigmillar and its Environs with Notes on the Topography, Natural History and Antiquities of the District (1892, George Lewis & Son, Selkirk) p.214

[35] Caledonian Mercury 10 May 1804, p.1

[36] Caledonian Mercury 23 December 1813, p.4

[37] Daily Review 28 November 1879, p.3

[38] The Scotsman 11 September 1869, p.8

[39] Inverness Courier 28 February 1844, p.2

[40] The Witness 21 February 1844, p.2

[41] Caledonian Mercury 17 October 1829, p.2

[42] Edinburgh Evening Courant 20 January 1866, p.8

[43] Tom Speedy, Craigmillar and its Environs with Notes on the Topography, Natural History and Antiquities of the District (1892, George Lewis & Son, Selkirk pp.234 – 239

[44] Edinburgh Evening News 13 March 1878, p.2

[45] Caledonian Mercury 24 March 1808, p.4

[46] Musselburgh News 12 August 1892, p.6

[47] Glasgow Herald 8 February 1875, p.4

[48] Musselburgh News 17 January 1893, p.6

[49] Ewan Gibbs, Coal Country: the Meaning and Memory of Deindustrialisation in Post-War Scotland (2021, University of London Press, London) pp.93 – 99

[50] Musselburgh News 09 August 1889, p.6

[51] Edinburgh Evening News 28 May 1892, p.2

[52] Ian McDougal (ed.), Mid and East Lothian Miner’s Association Minutes 1894 – 1918 (2003, Lothian press, Edinburgh) pp.46 – 47

[53] Ewan Gibbs, ‘Historical tradition and community mobilisation: narratives of Red Clydeside in memories of the anti-Poll Tax movement in Scotland’

[54] Ibid. p.39

[55] Ibid. p.50; p.58

[56] Ibid. p.323

[57] Ibid. p.383